Data Poverty Lab report: addressing data poverty for care-experienced young people

Written by Data Poverty Lab Fellows, Dr Becky Parry and Charlotte Elliott, this report explores how data poverty impacts care-experienced young people - and how it puts them at risk of missing out on creative opportunities.

Data poverty prevents some young people from accessing creative opportunitiesback to top

In early February 2023 new programmes of film screenings and film education for children were announced by the British Film Institute (BFI).[1] The aim of this investment of over 14 million pounds (National Lottery) is to engage wider communities of young people, help ignite their passion for screen culture and increase knowledge of a range of creative careers. This is an important policy shift that recognises the importance of film as a creative medium for children. As the three new programmes of work get underway, it is important to consider the way that data poverty can mean some young people miss out on new opportunities like these in ways that perpetuate inequities. This article aims to provide insights into the impact of data poverty on care experienced young people especially, offering strategies to help ensure this impact does not prevent young people from missing out.

What is data poverty?back to top

Data poverty is experienced by those individuals, households or communities who cannot afford sufficient, private and secure mobile or broadband data to meet their essential needs.[2] The four main causes of data poverty are poverty, unstable housing, barriers to securing data contracts and unstable employment. Those most impacted by data poverty include people who are: homeless, care experienced, refugee status, disabled, children, over 65, unemployed or experiencing other types of poverty.[3] Data poverty, therefore, impacts on the most marginalised young people in fundamental ways that are not well understood, and which create and compound intersectional disadvantage especially in relation to education. One quarter (25%) of children and young people, participating in the Nominet Digital Youth Index 2022 survey, rely on out-of-home internet connection to stay connected, indicating that this is a wide and pressing cause of inequity.

Data poverty in educationback to top

The current increase of online learning environments in schools, relies on students being able to access high quality and fast broadband. Students who do not have this access will not be able to access the learning and support provided by their teachers.[4] Often online learning ‘user interfaces’ are optimised for computer use, but many young people access them via smartphones. This impacts on the quality of the experience and is a barrier to learning. Data poverty, therefore, fundamentally limits access to education, compounding wider social inequalities and creating a digital divide amongst young people in education. There is also evidence that children and young people with care-experience face additional challenges online in relation to wellbeing and safety, for example vulnerability to internet scams and being victims of cyber aggression.[5] It is important that arts and cultural organisations do not compound these challenges and inequities in their work with young people and it was this concern that informed the project presented here.

The Data Poverty Lab Fellowshipback to top

This Data Poverty Lab Fellowship was undertaken by the author, (Dr Becky Parry) with Charlie Elliott and young people from Affinity 2020 for a period of six months in 2022. The research, funded by Good Things Foundation and Nominet, aimed to find out how care experienced young people were impacted by data poverty when trying to access creative or arts opportunities. The project took place in Rotherham, where preparations are being made to become the world’s first Children’s Capital of Culture in 2025, with a strategic aim to regenerate through sector growth in the creative industries. 56.6% of children and young people, in Rotherham, live in the 30% most deprived areas nationally,[6] so understanding the barriers young people face in terms of accessing creative and cultural opportunities is critical. The young people who took part in the project were at a transitional phase of setting up homes independently in Rotherham with support from Affinity in relation to education, employment and training.

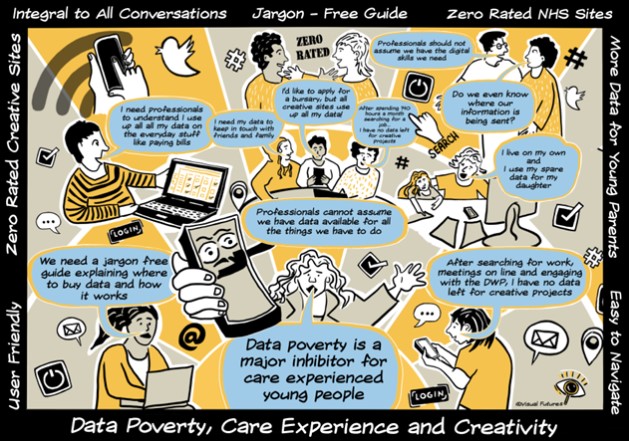

Creative methods to explaining experiences of data povertyback to top

Rather than undertake traditional research methods, we used a media production approach to enable the young people to reflect on, discuss, share and explain their experiences. The results of this process are summarised in the visual below co-created with visual artist and researcher Liz Churton. A podcast of interviews with creative professionals was also created with support from Sheffield Live and sound designer Jake Parry. The insights we share about the impact of data poverty reflect the experiences the young people in this group discussed with Charlie Elliot, in her role as advocate and ally. The suggestions for tackling data poverty resulted from investigations the group undertook as a result of these discussions, for example, in trying to resolve individual issues the group finding out about zero rated websites.

Experiencing data povertyback to top

For the care experienced young people in this group, the issue of data poverty is complex and constitutes a challenge everyday:

After spending 140 hours a month searching for a job, I have no data left for creative projects.

(Care Experienced Young Person)

It was clear that the young people had clearly defined priorities, including paying the bills, keeping food in the cupboard, finding work and maintaining contact with support workers. The data they had access to, was therefore quickly used up on finding work, education and training in order to take responsibility for their own lives. Every single one of these processes required the use of data. As Data Poverty Lab Fellow, Kat Dixon, demonstrates, good internet access is ‘elemental to living life in the UK.[7] At the start of this project, none of these young people had access to affordable, good quality broadband and although the local authority was keen to help, no long-term strategic solution has yet been implemented. Under 18s were especially at risk due to ineligibility for more affordable broadband contracts, leading them to take on more expensive smartphone contracts.

The second priority in use of data was keeping in touch with friends and family socially. In one of the sessions one of the care-experienced young people told us, that if she had more data she would ‘just use it to talk to her friends,’ implying that she recognised this might not be seen as an essential use. This was an important reminder that young people may need to be reassured that they have rights in relation to communication and maintaining connections with friends and family.

Asking if data poverty prevented the group from accessing arts and creative opportunities revealed that the more ‘everyday’ challenges [8] were, of course, more pressing:

I live on my own, so I use my spare data for my daughter.

(Care Experienced Young Person)

It is also important to say that the group had limited experience of accessing the subsidised arts, culture and creative sector either locally or nationally. This meant that our discussions focused on the way data poverty limits access, rather than engagement in new creative opportunities. However, there are also important lessons those of us in the arts, interested in inclusion and the growth of a diverse creative industry sector, need to learn from. Above all else, young people recommended that when we make creative / arts experiences available to young people (or any resource or opportunity):

Professionals should not assume young people have data to do all the things we have to do!

We need to remember too, that a sustained lack of data impacts on the development of digital skills that it is often assumed young people already have, for example video editing or photography.

Ideas for tackling data poverty which emerged from young people taking part in this project include:

- a jargon free guide to where to buy and access data.

- provision of zero-rated websites for services such as the NHS

- more zero-rated sites, especially for public services

- support in accessing affordable broadband at home to care experienced young people.

Is data poverty causing fear or danger of missing out?back to top

In the 21st century the concept of FOMO, fear of missing out, is frequently attributed to young people. The term made it into the Oxford English dictionary in 2013 and is defined as ‘a feeling of worry that an interesting or exciting event is happening somewhere else.’ But what if some young people are right to feel they are missing out? What if we swap the word fear for danger, in order to acknowledge that young people are at risk of exclusion. If they are care experienced, in the justice system, homeless or disabled, they are in danger of missing out. FOMO might well be a quite logical response to being excluded. I propose that DOMO (in danger of missing out) could be a helpful way of rethinking how we include young people in the creative and cultural sector and how we make activity accessible to them.

Data poverty puts young people in danger of missing out on new creative offers by arts and cultural organisations. If we are serious about addressing inequity, we need to address this urgently.

What can people do to reduce data poverty barriers?back to top

People designing and running arts, culture and creative projects:

- How will care experienced young people find out about and access our offer?

- How much data does the activity I am offering require? Is it too much? Is there an alternative way for young people to access it?

- Are we incorrectly assuming young people have the skills they need to access and apply?

- If the activity is costly, even where bursaries are offered, do these require further use of mobile or broadband data, or a suitable device, or digital skills?

- Is our online user interface smartphone friendly?

- Have we checked in with the Nominet Digital Youth Index[9] where information about the digital lives of young people in our region is available to help us plan?

- Have we connected with organisations working with young people who are likely to be impacted by data poverty (and digital exclusion), in order to invite the young people they work with to participate?

People funding or commissioning arts, culture and creative projects:

- Have we raised awareness of the potential negative impact of data poverty in our commissioning or funding process, and set out expectations around this?

- Are we valuing and supporting organisations who seek to address this issue in our commissioning or funding process?

- Are we signposting organisations to consider joining the National Databank run by Good Things Foundation to help tackle the impact of data poverty on access to and participation in arts and creative opportunities?

People supporting care experienced young people in a digital world:

- Have we made local creative and cultural organisations aware of our organisation and the role we play in supporting care experienced young people?

- Have we considered our organisation’s role and responsibilities in ensuring care experienced young people have access to affordable broadband and data?

- Have we sought strategic support from the local authority or other organisations (like the National Databank) to ensure care experienced young people have access to affordable broadband and data?

- Have we given care experienced young people opportunities to express an interest in engagement in arts and creative activity locally and nationally? Are these opportunities accessible via non-digital as well as digital channels?

There are some issues raised in the asking these questions that may be more challenging to answer. But if each sector addresses these issues early, ensuring they are informed of support that is already in place, the impact of digital poverty can be tackled. A focus on data poverty can also help build understanding of how to overcome further barriers to participation, by connecting arts and cultural organisations with the ‘wider communities’ public funding is designed to reach.

Next stepsback to top

Use the visual and the question prompts to reflect on your practice and planning.

Listen to the podcast, made in partnership with Sheffield Live here.

About this articleback to top

This article was written by Dr Becky Parry to share insights from the Data Poverty Lab Fellowship held by Charlie Elliott (Director, Affinity CIC) and Dr Becky Parry. The fellowship was supported by Good Things Foundation with Nominet in 2022.

Referencesback to top

- https://www.bfi.org.uk/news/national-lottery-education-investment-5-18-year-olds

- Lucas, P, J., Robinson, R. and Treacy, L. (2020). What is Data Poverty? Nesta

- Cripps, E., Lucas, P, J. and Robinson, R. (2021). Making Connections: Community-led action on data poverty. Local Trust

- Dilberti, M., Doan, S., Henry, D., Kaufman, J, H., Stelitano, L. and Woo, A. (2020). The Digital Divide and COVID-19: Teachers’ Perceptions of Inequities in Students’ Internet Access and Participation in Remote Learning. RAND Corporation, RR-A134-3: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-3.html

- https://www.internetmatters.org/inclusive-digital-safety/research-and-insights/family-factsheet/

- https://moderngov.rotherham.gov.uk/documents/s27549/Child%20Poverty%20appendix.pdf

- https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/insights/internet-periodic-table/

- Keegan Eamon, M. (2004). Digital Divide in Computer Access and Use between Poor and Non-Poor Youth. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 31(2), 91-112.

- https://digitalyouthindex.uk/

About the Fellowsback to top

Dr Becky Parry is a lecturer in Digital Literacies at the University of Sheffield who researches youth media and youth media productions. Becky is a Data Poverty Lab Fellow and was awarded a fellowship in Spring 2022 to examine one of three research themes with the Data Poverty Lab.

Charlotte is an Executive Educational Leader and Social Entrepreneur, who is the CEO of Affinity 2020 CIC in Rotherham. Charlotte is a Data Poverty Lab Fellow and was awarded a fellowship in Spring 2022 to examine one of three research themes with the Data Poverty Lab.