Partnership working to promote digital inclusion for health: Approaches to addressing digital inclusion in your area

This report was conducted in partnership with NHS England’s Primary Care and Community Transformation and Improvement team and the Local Government Association (LGA) Digital Inclusion Network, on behalf of the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Health and Wellbeing Alliance.

How to use this report

This report is intended as a learning resource and practical guide for local authorities and primary care professionals who are working in partnership to promote digital inclusion for health.

Informed by the experiences of local authorities, the report will help you to: learn about the opportunities and benefits of working together; identify barriers and enablers; assess the maturity of your own partnership; and identify practical steps to catalyse your partnership journey.

Watch, download or read the full report

A version of this report is available to download on the right of this article, alongside a toolkit. Alternatively, you can watch the launch of the report below, or read the full text-version on this page.

In this webinar, you will be introduced to a maturity model for partnership working on digital inclusion, which provides you with practical next steps, case studies and top tips to help you progress on your journey whatever stage you are at.

Executive summaryback to top

This report explores how local authorities in England are collaborating with primary care to promote digital inclusion for health. The findings are based on research conducted by Good Things Foundation with Better Places, in partnership with NHS England’s Primary Care and Community Transformation and Improvement team and the Local Government Association (LGA) Digital Inclusion Network. The research was conducted on behalf of the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Health and Wellbeing Alliance, a partnership between voluntary sector representatives and the health and care system.

Building on interim findings published in July 2024, and drawing on interviews with leaders and digital inclusion managers from 16 local authorities, the report identifies key priorities, challenges and enablers for partnership working. It shows that while motivations may differ – primary care partners often focus on digital access to healthcare services, while local authorities are more focused on social determinants of health – there is a strong, shared commitment to working together. The report also provides practical insights and a four-stage maturity model to help local areas assess and plan their partnership journey.

Key findingsback to top

- Local authorities are committed to digital inclusion across five key domains: access to devices and data, digital skills and confidence, beliefs and trust in digital tools, leadership and partnership working, and the accessibility of online services. Their work often aligns with the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion, while also recognising digital access as a wider social determinant of health.

- Partnerships benefit from strong leadership, connector roles across systems, and trusted relationships with VCSE organisations that work closely with people and communities at risk of digital exclusion. Data and insight, particularly when shared between partners, can guide resources and help demonstrate impact. Funding is both an enabler and a barrier – many initiatives are sparked by short-term grants, but longer-term sustainability relies on embedding digital inclusion for health into wider strategies.

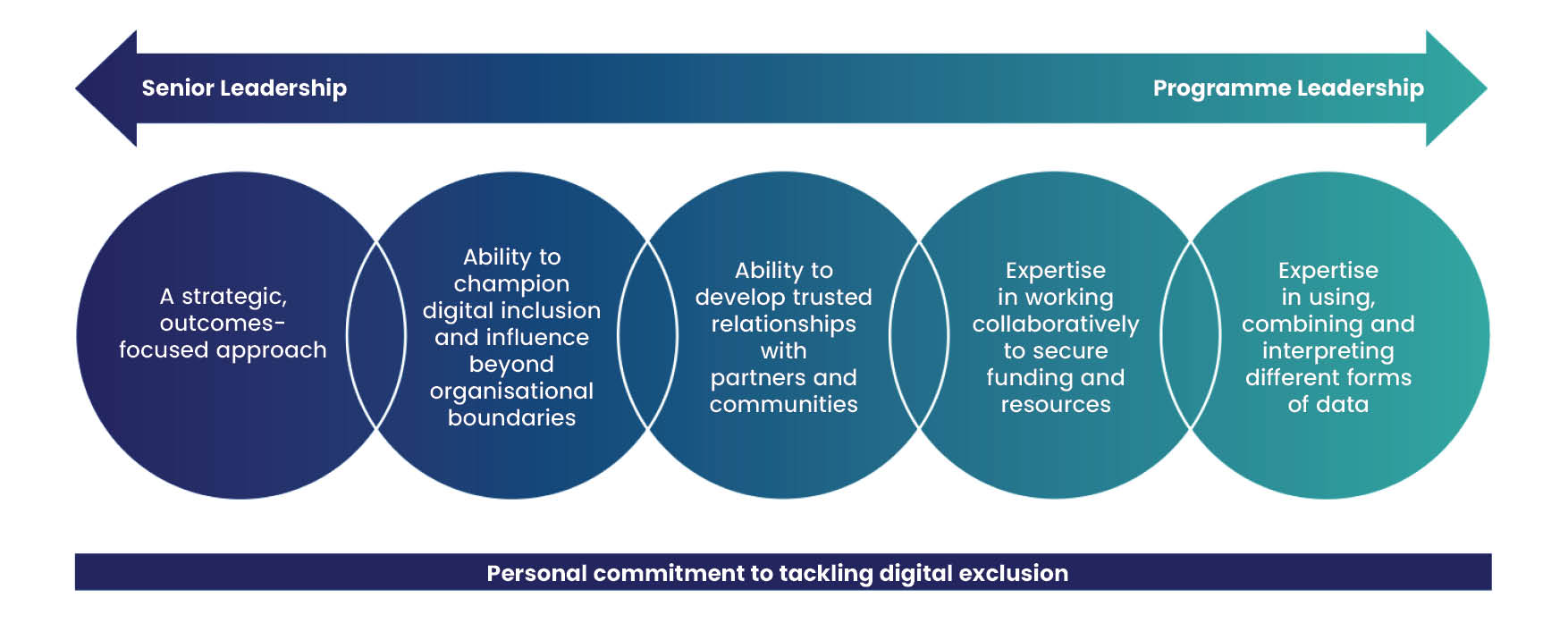

- Local authority and primary care partners require a range of skills, capabilities and attributes to work effectively together. These include: a strategic, outcomes-focused approach; an ability to work flexibly and influence beyond organisational boundaries; an ability to develop trusted relationships with partners and communities; expertise in working collaboratively to secure funding and resources; and expertise in using, combining and interpreting different forms of data.

Key recommendationsback to top

While the report highlights a range of opportunities to make progress, we suggest starting in three key areas:

- Nurture local authority engagement with primary care networks: To accelerate progress on place-based partnership working to promote digital inclusion for health, there should be a focused effort to support local authorities and primary care networks within a Place to work more effectively together. While in some cases, primary care networks are well placed to facilitate effective partnership working, others have less well-developed infrastructure to support this. In these instances, relationships between local authorities and primary care networks are relatively underdeveloped in comparison to engagement with integrated care boards and/or individual primary care providers (for example, GP practices).

- Support local authorities to further their understanding of primary care: The research highlights that the success of partnership working often depends on how well local authorities understand structures, working practices and priorities within primary care. To reduce barriers to working together, local authorities may benefit from support to deepen their knowledge of where opportunities exist to collaborate with primary care partners.

- Enable local authority and primary care teams to collaborate using data: Local authorities and primary care partners alike benefit from access to local data about digital inclusion, and the ability to leverage it building evidence-based strategies on digital exclusion. Training, resources, and partnerships with others such as universities or businesses, may help to build confidence, capability and capacity to identify and use data to support collaboration.

Introductionback to top

This report explores local authority leaders and managers’ experiences of engaging and working with health partners in primary care to promote digital inclusion for health. It builds on interim findings published in July 2024, which focused on local authorities who are already working in partnership with primary care. This final report brings new perspectives from participants in local authority leadership roles, as well as local authority digital inclusion leads at an earlier stage of working alongside primary care to promote digital inclusion for health.

The findings are based on research conducted by Good Things Foundation with Better Places, in partnership with NHS England’s Primary Care and Community Transformation and Improvement team and the Local Government Association (LGA) Digital Inclusion Network.

The research was conducted on behalf of the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Health and Wellbeing Alliance, a partnership between voluntary sector representatives and the health and care system.

Why we conducted the researchback to top

The use of digital approaches within primary care can be a powerful enabler of health and wellbeing. Sometimes described as the front door to the NHS, primary care is the first point of contact with healthcare services for most people.

Digital tools can make it easier to access primary care services, improve patient experience, and give people greater control over their own care and play a part in reducing health inequalities. But unless these benefits are shared by everyone, they can also deepen existing health inequalities by improving experiences of primary care for some while creating additional barriers for others.

NHS England aims to address this through its framework for action on digital inclusion, which emphasises the importance of ‘collaboration at different levels and across sectors, particularly with local government, the voluntary sector, and grassroots community groups’.

NHS England Primary Care and Community Transformation and Improvement Team (PCTI) have been leading improvements to the usability and accessibility of digital tools used in primary care. They undertake user research focused on understanding the needs of less digitally confident and less literate patient groups and use this evidence to define patient needs, create digital standards and define inclusive implementation approaches.

Local authorities also play a significant role in contributing to digital inclusion for health, often working with people who are at particular risk of digital exclusion, and providing many services that have a direct impact on the health and wellbeing of communities.

Within this context, our research aims to understand the perspectives of local authority leaders and managers when it comes to collaborating with partners in primary care. The findings will contribute to insights for NHS England and others around the practical challenges of turning policy and guidance into improved experiences around digital inclusion for people and communities.

Our approachback to top

We interviewed digital inclusion leads and senior leaders from 16 local authorities in England to explore their experiences of engaging and working with primary care (including integrated care boards and primary care networks) to promote digital inclusion for health. This includes four senior leaders and eight digital inclusion managers from local authorities with more established approaches to working with primary care, as well as six at the very beginning of (or yet to start) their journey of working together.

The participating local authorities varied by:

- Structure; including unitary, metropolitan and county councils, and a London borough

- Geography; including local authorities from different regions, and in both rural and urban areas

- Relationship to NHS boundaries; including local authorities that have coterminous boundaries with their local integrated care system, and those that do not.

We tested our findings through a series of workshops with the Local Government Association (LGA) Digital Inclusion Network to ensure we heard the perspectives of digital inclusion leads from a broad range of local authorities. However, as an exploratory piece of research we recognise that the findings may not be representative of the experiences of all local authorities, or all local authority partnerships with primary care.

Digital inclusion prioritiesback to top

All of the local authority leaders and managers we interviewed are proactively working to promote digital inclusion to help ensure that people living in their area can access public services and participate in community life. As set out in Table 1, our research suggests that they are acting on digital inclusion across five key domains, which correspond to those set out in the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion.

| Domain | Priority |

|---|---|

| Access to devices and data |

Local authority interviewees highlighted that the cost of internet-enabled devices (e.g. smartphones, tablets and laptops) and access to Wi-Fi and mobile data is prohibitive for many people and communities. In response, some have developed initiatives to recycle and reuse donated devices, promote social tariffs, establish equipment loan schemes, and provide free devices and mobile data through, for example, the National Device Bank and National Data Bank run by Good Things Foundation. |

| Skills and capability |

Local authority interviewees recognise that the breadth of their service provision creates valuable opportunities and touchpoints to promote the development of digital skills, capabilities and awareness of benefits within their area. Many of the local authorities we interviewed deliver volunteering programmes in community spaces such as libraries and community centres, and in some cases digital champions are also embedded within health and care settings. Other local authorities have co-located with health services to create digital health hubs, providing a range of social prescribing and digital inclusion support all in one place. |

| Beliefs and trust |

Local authority interviewees recognise the importance of building trust and confidence in digital approaches, particularly within the context of health. For example, they identified that within some communities, there is concern about how patient data might be used. Some prioritise targeted communications towards the most at-risk people and communities. However, they appreciate that they cannot address this alone. Just as the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion recognises libraries as an important community touchpoint, local authority interviewees perceive that primary care providers play an equally important role. For example, local authority interviewees talked about the ways that general practice can help to identify people at risk of digital exclusion and make appropriate referrals, as well as providing spaces for digital champions to engage with patients. Local authority interviewees also place a strong emphasis on the relationships that VCSE organisations have with people who are at greatest risk of digital exclusion. These relationships are pivotal in helping to understand and fill gaps in beliefs and trust with people who have lived experience. |

| Leadership and partnerships |

Local authority interviewees identify leadership as a key enabler of effective of digital inclusion for health, bringing together the necessary expertise, coordination, and funding to drive success. Depending on their stage of maturity, some local authorities place significant emphasis on building cross-sector collaboration with NHS partners and VCSE organisations, and building meaningful partnerships with private sector organisations who may commit funding and other resources. |

| Accessibility and ease of using technology and key digital journeys and services |

Some of the local authority leaders and managers we interviewed are focusing on optimising and improving the accessibility of their digital and online platforms. For example, this includes ensuring that digital inclusion is considered within their approach to service design and understanding of population needs. However, this was less commonly referenced among local authority interviewees in comparison to other domains, whereas it occupies a more prominent role within the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion. This discrepancy may be explained by the relative importance attached to digital transformation by primary care partners in comparison to local authorities. |

* Adapted from the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion.

Priority groups and communitiesback to top

The local authority leaders and managers we interviewed are choosing to focus their finite resources on supporting people and communities who are most likely to be digitally excluded. Frequently, they determine their priorities based on the digital capabilities of people living in their area, rather than by demographic characteristics. For example, one local authority distinguishes between people who are ‘digitally confident’, ‘digitally excluded’ or ‘digitally averse’. Others use similar groupings based on levels of digital literacy.

“It's open to all, but some things we're doing are quite targeted. We do have priority demographics and geographical areas… [it’s] kind of a combination of where those populations are and where we can deliver operationally.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

As set out in Table 2, interviewees told us that where their local authority chooses to focus on specific priority groups, again these are closely aligned to those identified within the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion. Some local authorities go a step further, using the NHS Core20PLUS5 approach to tackling health inequalities as the basis for prioritising their activities.

This approach recognises that there is significant overlap between Core20PLUS5 priority groups and the most digitally excluded communities, especially inclusion health groups for whom digital exclusion is likely to be particularly entrenched.

Alongside other challenges, low literacy levels among inclusion health groups can be a particular challenge in a world that is moving online where reading, comprehension and expressing needs through written communication are a significant shift from verbal communication, in person and over the phone.

The NHS framework for action on inclusion health explores measures that might be used to address this, for example presenting information using short films and pictures, and using online tools to translate to different languages.

“When we’re talking about digital exclusion, 99% of people are online. ‘So it's like, why should I bother? Why should I care?’ But 99% of homeless people are not digitally included, 99% of care home residents are not digitally included. So, a lot of our work is making the case in deepening the understanding of the impact of digital exclusion on specific communities.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

| Characteristic | Priority groups |

|---|---|

| Age | Older people, especially people over 75 years old (also children and young people, and people over 40 with few or no qualifications, who are not specified within the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion). |

| Ethnicity | People from Black and minoritised communities. |

| Language | People who are less fluent/confident in using and understanding the English language. |

| Socio-economic disadvantage | People who are unemployed, people on low incomes, people with lower levels of literacy, people with few or no qualifications, single parents, carers people living in areas of high deprivation. |

| Health | People with long-term health conditions, people with mental health issues, people with physical and learning disabilities, care home residents. |

| Social exclusion | Veterans, people experiencing addiction, people experiencing homelessness, people experiencing domestic abuse, refugees and people seeking asylum. |

| Geography | People living in areas with inadequate broadband and mobile data coverage. |

* Adapted from the NHS framework for action on digital inclusion.

Relationships with primary careback to top

Local authority leaders and managers with existing relationships with primary care said they are working with a variety of partners, including integrated care boards, primary care networks and individual primary care providers (principally general practice). These interviewees expressed that there are clear and distinct benefits to working with primary care partners at each of these levels. Often, local authorities work with integrated care boards to coordinate strategy and resources for digital inclusion. By contrast, local authorities perceive that primary care networks help to increase community reach and facilitate delivery of digital inclusion activities.

Leaders and managers from local authorities at an earlier stage agreed but place a stronger emphasis on customer needs and confidence (for example, helping people to engage with the NHS App), rather than thinking more strategically about the efficiencies and opportunities afforded by working together.

Starting the journey of working togetherback to top

Local authority leaders and managers who are already working with primary care told us their partnerships had been initiated in a variety of ways. Some were initiated through top-down strategic planning, while others developed organically through mutually beneficial projects and activities.

Often, they felt they had been responsible for reaching out to health partners in the first instance, sometimes looking to engage them in specific programmes and initiatives, and at other times to open up more exploratory conversations about opportunities to work together. For example, one local authority started working with primary care after setting up a device donation scheme aimed at tackling digital exclusion, to which GP practices were invited to contribute. In another instance, ICB and primary care networks were invited to contribute to conversations about improving citizen experience, as part of the local authority’s efforts to enhance how residents interact with digital services more effectively.

Alongside reaching out to primary care, local authority leaders and managers are also seeking out ways to bring primary care professionals into their own conversations about digital inclusion for health. For example, one local authority leader spoke about the importance of primary care representation on their Health and Wellbeing Board, which has oversight of their digital inclusion plan.

“The Health and Wellbeing Board works well in terms of bringing together the different partners and we do have a good relationship with the local NHS”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

It is important to note that while the local authority interviewees involved in this research ultimately developed (or are seeking to develop) partnership approaches to working with primary care, this is not always their starting point. For instance, one had first established a relationship with their integrated care board, only becoming directly engaged with primary care after securing funding for a joint project involving GP practices.

Some local authority interviewees told us they have found it difficult to establish relationships with primary care networks due to frontline pressures within healthcare. Others told us that they had some success directly engaging with primary care networks, for example with a view to situating digital champions within primary care settings. However, some had not experienced partnerships being initiated by primary care networks themselves.

In these circumstances, local authority leaders and managers sometimes choose to focus their resources on working with a smaller number of individual primary care providers, for example GP practices. An example of this type of partnership might include the co-location of digital champions within GP practices. Others are working more strategically with their integrated care board(s), for example focused on improving the ‘user journey’ between local authority and primary care services for people who are digitally excluded.

Aligning your prioritiesback to top

While it is encouraging that local authority and primary care partners have many priorities in common, some local authority leaders and managers reflected that they may have different starting points for thinking about digital inclusion.

Interviewees from local authorities at all stages in their relationships with primary care perceive that primary care partners are focused on digital inclusion to help patients benefit from digital healthcare services. For example, this might include using GP websites and the NHS app to make appointments, order prescriptions, or access medical information.

In contrast, interviewees perceive that local authorities take a broader view, identifying digital inclusion as a key enabler in tackling the wider social determinants of health. For example, their approach may be aligned to, variously, poverty reduction, adult social care, housing or public health. This can create challenges when it comes to align priorities around digital inclusion.

“Our digital inclusion strategy did not start from a digital transformation standpoint. It is because we understand it as a social determinant for health inequalities. We want to be preventative, so we want to do digital inclusion.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“Our approach to digital inclusion… is very much seen as a social inclusion programme, rather than a transformation programme. That’s a really important distinction.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“We report on the social outcomes that are achieved through digital inclusion. That could be improved health, access to employment, safety and security for people who are homeless or fleeing domestic violence, reduced social isolation for people in care homes, and so on.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“Everybody says we want to address the wider determinants of health, but the NHS is very much focused on its targets… so, although there's widespread agreement we need to move to early intervention and prevention, the money goes to urgent care.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

However, interviewees told us that while it can sometimes be challenging to align priorities, and that there is significant groundwork to be done in mobilising work in partnership, there is a genuine appetite to work together. In particular, this appetite is growing as the need for digitally included communities becomes increasingly pressing, alongside the recognition that the communities most in need of support are also those most likely to require support from local authority and primary care services.

“I wouldn't say it's a natural partnership because we each serve separate purposes. But you can't have one without the other, if that makes sense. So, there's a lot of rationale, reason and commitment to joined-up working.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

“There are benefits for all of us here, very often those people who might be the ‘more expensive’ clients for health and are the same for local authorities, so it’s in all our interests to work on this together.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

A maturity model for shared action on digital inclusion for health back to top

As set out in Figure 1, the different ways that local authority and primary care partners work together can be understood as a maturity model for shared action on digital inclusion for health. We have categorised this into four stages of maturity: emergent, engaged, established and embedded. The local authorities that participated in this research vary in terms of where they sit on this maturity scale, and this can take several years to develop. There are also nuances within individual local authorities, for example, they may be at varying stages of maturity across different domains.

| Emergent | Engaged | Established | Embedded | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities |

|

|

|

|

| Reach |

|

|

|

|

| Governance |

|

|

|

|

| Funding |

|

|

|

|

| Impact |

|

|

|

|

| Stakeholders |

|

|

|

|

Enablers of successback to top

We identified five key enablers that underpin effective and impactful partnership working between local authorities and NHS partners in primary care. These are:

- Proactive leadership supported by a clear vision and strategy

- The presence of connectors and catalysers

- Funding and resources

- Data and learning

- Combined local knowledge.

Proactive leadershipback to top

The local authority leaders and managers we interviewed told us that proactive leadership is vital to developing a whole-system approach to digital inclusion for health. While approaches to leadership vary between local areas, we identified three common ingredients:

- A dedicated team or group with responsibility for cultivating a shared sense of purpose and cohesion about what it is possible to achieve by working in partnership

Local authority interviewees said this is important because leadership of digital inclusion is often highly distributed, involving many different stakeholders. They identified that it is helpful, where possible, for this to be supported through strong political leadership, by councillors who are willing to advocate externally and secure buy-in to partnership approaches to promoting digital inclusion.

“[Partnership working] needs that long-term leadership commitment to saying ‘digital inclusion is really important to us as an area’. We do need to be making sure that we are spending public money in the right ways and the continued check that digital inclusion programmes are delivering their intended outcomes is really, really important. But fundamentally that has to be driven from the top.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

“That leadership, that’s a really important thing. It almost doesn't matter where that sits. That could sit in the Council. It could sit within the NHS. It could sit within the third sector. What matters more is the licence that team or person is given to work across sectors. It's that ‘one team approach’ mindset.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“The leadership’s actually really important… how you work together, how you get on together, whether your values align, whether your perspective of a problem aligns. Making time to talk those things through with each other.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

“I'm really lucky that we've got a very brilliant councillor who holds digital inclusion as part of their portfolio. She's a fantastic ambassador for digital inclusion. Having an ambassador is critical.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

- Clear governance and accountability measures, with financial and practical support at the right level wherever it is needed across the system

Local authority interviewees perceive that digital inclusion projects are more likely to succeed if they are connected into the corporate governance structures of the local authority and/or primary care system, bringing about the ability to invest and plan over the long-term.

“The most important thing to me when I started engaging with the digital inclusion partnership was getting it recognised within our corporate governance structure. And I decided the Health and Wellbeing Board was where it needed to be, because it has that representation from across the council and from health partners. And the police are also there, and the fire service and the housing providers. So that it was seen as a system-wide issue, not something that was just a local authority issue, or just a health issue.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“Digital inclusion, at this point in time, is still regarded this thing on the side… it sits in the digital space because it's got the word ‘digital’ attached to it. But actually, it’s about [meeting the needs of] the customer, and it just happens that all of that work is facilitated by digital things.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

- Cross-sector collaboration, with a clear emphasis on co-design and co-production

Working alongside communities and community organisations is perceived to be critical to the development of successful approaches to digital inclusion for health. This requires an ability to work flexibly across organisational boundaries and a commitment to listening and responding to ideas from a variety of sources.

“A strand of our new digital inclusion strategy will focus on primary care and social prescribing. We're currently recruiting all sorts of organisations and partners to come along to help us, because we need an input from all of them to shape what we do and how we do it.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“There’s a lot of innovation happening with the community sector. Our role is simply to pull all this knowledge together to make it more meaningful.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“For me, it’s about organisations taking collective ownership, saying [for example] ‘the council is leading on a device scheme, let’s all get behind them on that’, rather than pulling in different directions.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

In practice: Proactive leadership on digital inclusion for healthback to top

One local authority is working at a strategic level with services and organisations across the health and care system to promote digital inclusion for health. The digital inclusion team has a leadership role to strengthen the area’s digital inclusion infrastructure and increase its digital inclusion capacity. The team is responsible for developing the strategic approach, driving the agenda, convening networks, creating partnerships, and building capacity within organisations and across sectors. The local authority highlights the importance of the team’s visibility and connections across their geographical footprint as an important driver of change.

“If the system can’t easily answer the question, “Who leads digital inclusion in your area?” then that should be the top priority.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

In turn, this has helped to create a shared sense of leadership, by supporting colleagues to take a more active interest in, and ownership of, digital inclusion as an issue for their communities or within their organisations. The team also helps professionals to develop a sense of purpose and cohesion, so they understand digital inclusion in the context of their organisation and the local authority footprint.

Rather than working directly with people who are digitally excluded, the local authority supports organisations who already have relationships with people and communities, helping them to develop their approach to digital inclusion. At a system level, they also have key areas of priority focus around which key stakeholders coalesce (for example, older people, and people with autism and/or learning disabilities).

This strategic model can be adapted to meet a wide range of outcomes, working with the partners who are best placed to identify the communities who may benefit from support. The approach has enabled them to attract funding from a wide range of sources, over and above the council and local NHS partners.

“If you don’t have a programme in place with recognised leadership, the outcomes will take longer to achieve. In those cases, the temptation is often to focus on outputs that are easier to achieve and easier to measure – the number of people downloading the NHS app or the number of people attending a digital skills session, etc. Our work is about building a sustainable digital inclusion support system across the area, so that people can get help when they need it, where they need it, from services and organisations they already know and trust.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Proactive leadership: top tips for getting startedback to top

- Prioritise what matters most: Partnerships take time to embed, and you don’t have to tackle everything at once. Instead, identify the most important goals you’d like to achieve through working in partnership, clearly communicate them, and use these priorities to focus your collaborative efforts.

- Find a senior leadership champion: Local authorities and primary care networks should each designate a strategic leader to drive digital inclusion initiatives. Local authorities might choose someone adept at building relationships with primary care and other stakeholders, ensuring that digital inclusion aligns with priorities like public health or adult social care. Likewise, primary care partners may appoint a senior leader who can liaise with local authorities and advocate for integrating partnership initiatives within NHS priorities.

Proactive leadership: top tips for senior leadersback to top

- Lead with personal commitment: Make your commitment to promoting digital inclusion visible to your teams and others. Demonstrate your drive to achieve more through working in partnership, seeking opportunities to align digital inclusion with existing strategic priorities.

- Use your platform to influence others: Emphasise the mutual benefits of partnership and foster a culture of collective responsibility for digital inclusion in health (i.e. it’s not ‘yours’ or ‘mine’, it’s ‘ours’). Ensure that digital inclusion is prioritised within key governance structures (for example, integrated care board working groups or local authority Health and Wellbeing Boards) so that it receives the necessary resources alongside your leadership efforts.

- Empower your teams: Aim to remove barriers for your teams when it comes to working in partnership. You might use your position to seek resources, facilitate collaboration and make connections, providing your team with the tools they need to build collaborative digital inclusion initiatives.

Connectors and catalysersback to top

Some of the interviewees we spoke to told us that their local authority had identified a key individual who adopted a connector role, taking responsibility for nurturing relationships and catalysing opportunities for local authorities and primary care providers to work together.

Connectors can be situated either within a local authority or within primary care, and are not necessarily senior leaders. However, through experience they bring (or develop) a high level of knowledge about digital services and provision within their geographical footprint. Some local authority interviewees identified that it is optimal to have connectors and catalysers at multiple levels, bringing additional strength to the partnership.

“The thing that has been to our advantage throughout this is the great working relationships that we have at multiple levels within the organisation. At chief executive level there is there has always been this very close-knit working relationship between the local authority and the chair of the primary care network, and that helps.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

Some local authority interviewees feel that, for colleagues who are not familiar with the landscape of primary care, it can be difficult to spot opportunities and know who to speak to. This is especially the case where local authorities and integrated care systems have non-coterminous boundaries, or in places where there is wide variation in approaches to digital transformation and/or inclusion among primary care partners.

Connectors therefore play an important role in helping local authorities and primary care providers understand each other’s work and priorities, helping to build systemic relationships, develop shared language around digital inclusion, and integrate services and provision. As a simple example, one local authority identified that their ‘connector’ helped to build relationships with primary care networks by engaging with GP practice managers rather than clinical leads, recognising the pressures on frontline health professionals. Others spoke about their ambition to nurture ‘place-based’ digital inclusion networks, focusing on developing best practice as well as more localised, solutions to specific problems.

“It's the million-dollar question, isn't it, how to get more out of existing resources. It needs people to do it, to drive it and to take on that mantle of saying ‘this really matters’. It's playing the connector role, joining up the dots. And because I've been working for the local authority for many years, I know a lot about who does what and where the gaps are. So that is obviously really helpful, because I can try and make those connections.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“There's so much activity in this space, so many organisations offering all this different, incredible stuff. But they don’t always talk to each other. So my ethos, when I first started was, let's not reinvent the wheel. I want to know exactly what's happening and where it's happening, and start thinking about how we can make what we’re all doing individually even better.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“There’s lots out there. There are so many different funding streams. What's helpful is almost that kind of matchmaking. We sometimes feel it that we're able to find a really good programme and we know the community well, we can make that meaningful connection.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

In practice: Connectors and catalysers in actionback to top

A digital inclusion lead in one of the local authorities we interviewed set about on their journey of connecting and catalysing action on digital inclusion in 2017, after joining a cross-sector digital inclusion task group comprised of members across NHS organisations, the local authority, VCSEs and faith groups.

The local authority estimates that up to 70,000 people in their area are either digitally excluded or lack basic core digital skills. The digital inclusion lead described the group as ‘doing some really important stuff, but it was working in a black hole so it couldn’t meet the scale of the challenge’.

Despite not having digital inclusion as part of their job title or formal responsibilities, the digital inclusion lead has supported the group to develop a digital inclusion plan in consultation with residents and stakeholders. The group has now been established as a Digital Inclusion Partnership operating on a permanent basis and is recognised within the local authority’s corporate governance structure via its Health and Wellbeing Board.

Close relationships with primary care commissioners and providers have been vital to this approach, with health partners involved at both implementation and strategic levels. Working alongside a range of other organisations, local authority and health partners have worked together to ensure the approach recognises digital inclusion as, ‘a system-wide issue, not something that is just a local authority issue, or just a health issue.’

“If you haven’t got that system stewardship, it might drift along with an occasional bit of emphasis. But it's one of these things that really needs some sustained effort and capacity over a period of time, so that we can really try and crack the nut together.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Connectors and catalysers: Top tips for getting startedback to top

- Identify who will coordinate your partnership efforts: While relationships between local authority and primary care teams do not necessarily need to be held by just one person, a coordinating role is often helpful. Sometimes, this is a dedicated position, and at other times part of a team member’s wider remit. Coordination will help you to ensure effective use of resources, make connections between individual projects and initiatives, and ensure that teams are well supported to deliver their objectives.

- Don’t reinvent the wheel: Go out and talk to partners and the communities you support, find out what they need and what’s already happening in your area. Seek opportunities to support and build on the work of others to promote digital inclusion for health.

- Collaborate and share: In the early stages of working in partnership, take time to share information and best practice, and gain an understanding of each other’s work. This will help you spot opportunities to work together, while ensuring that any new initiatives complement your existing activities.

Connectors and catalysers: Top tips for senior leadersback to top

- Find the right person and provide support: Connectors and catalysers don’t always need to be in senior roles, but as a senior leader, you have an important role to play in supporting them. Offer guidance, connections, and the autonomy they need to engage with and influence others effectively.

- Connect the strategic and operational aspects of partnership working: Building a network of people within your local authority who are passionate about promoting digital inclusion can strengthen your efforts. Consider how people in different roles, and at different levels of your organisation(s), could help to make the bridge between the operational and strategic aspects of working in partnership.

- Establish a clear governance framework: By integrating your partnership efforts into a governance structure, you can ensure that the right stakeholders are involved and accountable for the success of your digital inclusion initiatives. This might be a group focused specifically on digital inclusion, or one that already exists. For example, within local authorities this might be the Health and Wellbeing Board, and for primary care it might be your integrated care board. Consider what makes sense within your own local context and start from there.

Funding and resourcesback to top

The local authority interviewees we spoke to consider funding, where it is available, to be a significant enabler of digital inclusion for health. They anticipate that funding will become even more important over time, based on their perception that social and economic pressures, coupled with the rapid pace of technological change, may lead to increasing numbers of people becoming digitally excluded.

“What we've discovered over the 10 years that we've been doing this work is that it doesn't go away, it gets more each year. We need the underlying funding, so it's seen as business as usual and just ‘what needs doing’.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“The sustainability of digital inclusion programmes has to be there, because otherwise you have this stop-and-start approach which never really delivers impact… that needs that long-term leadership commitment to saying ‘digital inclusion is really important to us as an area’. We do need to be making sure that we are spending public money in the right ways and therefore the continued check that digital inclusion programmes are delivering what they their intent outcomes is really, really important. But fundamentally that has to be driven from the top.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

Some local authority leaders told us that, given the current financial climate, they are highly focused on reducing cost pressures. While they recognised that digital inclusion is an important enabler of service transformation, they highlighted that it can be difficult to make progress when there are immediate needs within statutory services.

“[Our local authority] is in a very tricky financial position, so some of our digital inclusion work has stopped… the measures that are being taken forward as a local authority at the moment are largely about cutting costs. However, there is more transformation that we can do… we need to much better understand who our customers are, improve our online services… digital inclusion plays into all of that.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

Doing more with lessback to top

Even where funding is not available, local authorities are often working creatively with primary care partners and other stakeholders to achieve success with limited resources. Others, particularly local authorities at the ‘emergent’ stage, said that aligning budgets for digital inclusion is often a ‘work in progress’, with digital inclusion teams making ongoing efforts to advocate internally for more strategic use of funding to tackle digital exclusion.

“One of the things that we're not worrying about too much at the moment is money, not because we've got any, but we think we can actually achieve quite a lot just by joining up stuff that's already happening and joining up partners across the system.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

One of the ways that local authority leaders and managers have been able to make the most of existing system resources is by leveraging funding from their private sector suppliers, who have made a commitment to creating social value as part of the local authority procurement process. For example, one local authority has worked with businesses to train social prescribers and care coordinators to become digital champions.

The interviewees who have taken this type of approach are positive about the potential benefits, although they also note the importance of ensuring that activity is meaningful to communities and not simply a ‘tick box’ exercise to secure funding.

“For me, digital inclusion and social value are like a power couple. Businesses can really help us solve some of this. Their part of the equation is the money bit, the devices bit, the connectivity bit, that we as local authorities often don't have the resource and capacity to be able to deliver.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“When we first started, we had very limited resources, so we had to look where we could be creative. One of the first things we did was look to the social value commitments of our own ICT suppliers… they often have quite good social value allowances, whether it's time or resources, but often they just don't know where to start.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead

Funding as a catalyst for working together – and its limitationsback to top

Many of the interviewees we spoke to talked about the importance of grant funding as a catalyst for generating new ideas and initiating collaborative projects with primary care partners. Particularly in the early stages of working together, local authorities characterise their partnerships with primary care as opportunistic rather than goal-driven, for instance designing a digital inclusion for health project in response to a specific funding call. Grant funding can come from a range of sources, principally charitable organisations such as Good Things Foundation and central government programmes.

Local authority interviewees feel that a significant limitation of grant funding, which is often time-bound, is that it raises community expectations about the type of provision they may be able to access without any guarantee that it will be sustainable. Similarly, a reliance on grant funding can incentivise local authorities to employ staff on a project-based, fixed-term basis, which in turn inhibits the development of longer-term relationships with primary care partners.

“[Grant funding] will give you a potential spike of activity while the funding is in place, but it won’t build a sustainable offer of support for the longer term. So a few people will benefit while the activity is being funded, and that’s not nothing. But what about the next cohort of people who need support after the grant has run out, and the next and the next…?”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“[We’re always thinking about] how we can fund our work without having to constantly make the argument each year about why we should be doing something, and shifting some of the costs of the team from project officer roles to permanent staff.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

In practice: How national funding is helping to tackle health inequalities through digital health hubsback to top

One local authority is working with their integrated care board to develop ‘digital health hubs’ to enhance digital inclusion and tackle health inequalities. ‘Digital health hubs’ can be community organisations, libraries and other locations which offer help to people to overcome barriers to digital inclusion so that they can access relevant information and tools to improve their health and wellbeing. The initiative is being delivered in partnership with over 50 voluntary and community groups, and a private sector network solutions provider.

Up to now, the project has been funded by the UK Shared Prosperity Fund and came about following a joint bid by the local authority’s digital inclusion and public health teams. Across 22 community buildings, voluntary and community groups commissioned by the local authority are developing a new digital architecture to extend Wi-Fi coverage to all public and staff areas. Alongside this, sensors have been installed to measure footfall and maintain the health and integrity of the buildings. Data is fed daily from the sensors into dashboards to measure Wi-Fi usage, the number of people accessing the building, humidity, temperature, atmospheric pressure and C02 concentration levels. Digital devices, databanks and online centres have been set up offering daily access to devices, free SIM cards and learning opportunities.

Over 30 voluntary and community organisations are now delivering daily activities designed to improve health and wellbeing, helping to join the dots between health services, the council, voluntary sector and the community.

“Our digital health hubs are connected into health. If someone is coming to a GP surgery, they can be signposted to a centre, and a digital champion will be able to sit down with them and say, ‘right, let's have a look at what you're interested in, let’s see what's available for you’”.

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Peer support is central to the model, via a network of people who have been upskilled to volunteer as digital champions. The digital champions are on hand to help out, build confidence and share their digital skills and learning with others, by showing people how to navigate around the web safely.

Funding as a tool for embedding practiceback to top

Within more established partnerships between local authorities and primary care partners, funding tends to play more of an enabling role. In these circumstances, funding is used to deliver on shared strategic priorities – with local authorities and primary care combining forces to make a business case for investment, fund business critical roles or pool resources to deliver collaborative initiatives.

“We now bid collaboratively for pots of money [with NHS colleagues], because it makes a better business case, and it doesn't matter who spends it.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Many of the interviewees we spoke to feel that a financial contribution from within the health and care system is critical to digital inclusion for health, particularly if initiatives delivered in partnership are to scale and grow. While some feel they have had a very positive experience of working in this way, others said they would welcome greater clarity about the respective roles and responsibilities of local authority and primary care partners. Local authority leaders and managers acknowledge that these responsibilities are likely to vary between contexts, and are flexible about how this might work in practice.

“Funding is massive. I absolutely would not downplay that. We’ve had money from various bits of the NHS, which has helped us to fund business critical roles.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“Speaking frankly, I think [partnership working with health] is hamstrung because we get very little funding from our ICB and we're doing a lot of work to support them… there's loads of benefits to being able to do things digitally but there’s not much cash coming out to support that.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Funding and resources: Top tips for getting startedback to top

- Highlight the ways that digital inclusion can catalyse other strategic priorities: Collaborate to make the case about the ways that digital inclusion can support existing work programmes. This will help to secure buy-in from a wider range of teams and services.

- Build on each other’s digital inclusion priorities: Within an NHS context, there is a strong focus on the uptake of the NHS App and other digital tools such as online consultation systems (digital access). General Practices and primary care networks are focused on establishing ‘digital front doors’ alongside telephone and in person contact routes, with parity across access channels, to support more inclusive access. Likewise, local authorities have their own priorities. Consider how you can bring the best of your expertise to maximise your impact.

- Align funding and incentives: Take time to identify potential funding sources and align incentives across partners. Consider how you can make the case for the long-term socioeconomic benefits for of digital inclusion for health.

Funding and resources: Top tips for senior leadersback to top

- Align digital inclusion with broader public service objectives: Ensuring that digital inclusion is seen as a key element of broader public services is a strategic lever for sustainable funding. This means aligning to strategic priorities for both local authority and health partners (for example, health inequalities and creating more digitally capable communities).

- Align with government priorities: Senior leaders should stay attuned to emerging governmental priorities and funding opportunities, particularly as devolution continues to evolve. Aligning digital inclusion efforts with changes across the external landscape can help you to secure additional resources and amplify your impact.

Data and learningback to top

The local authority leaders and managers we interviewed highlighted that effective use of data and experiential learning is critical to effective partnership working with primary care. They told us that the strategic use of data allows them to focus on the most important priorities, and helps them to be more responsive to evolving needs within their communities. Furthermore, data is important for accountability, helping local authorities to measure and communicate the sustainability and impact of their partnership work with primary care.

Using data and learning to determine prioritiesback to top

Local authorities commonly use the Digital Exclusion Risk Index (DERI), first developed by Greater Manchester Combined Authority, as a tool for identifying and supporting digitally excluded groups. They may complement this through use of national and regional datasets, published research, intelligence from local and regional groups and networks, as well as focus groups, surveys and impact assessments.

Particularly in more established partnerships, local authorities are effectively combining their own knowledge with data and insights from primary care. They told us that complementary data insights from NHS partners in primary care enables them to make greater use of a wider variety of population level data. In turn, this helps them to develop a deeper understanding of their communities, target their work in partnership with primary care more effectively, and improve how they report on outcomes.

“They [primary care partners] increase our ability to report outcomes because they have a whole load of data that sometimes, anonymised, they can share with us.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“[We are exploring] how we can use public health management data alongside some of our own data, to understand different areas of need and where our work would be best targeted… we are able to use our data to guide where provision needs to go.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Local authority interviewees shared that using existing data can often be more helpful than attempting to define and measure levels of digital inclusion among different population groups. For example, this might include population health management data showing the prevalence of certain long-term health conditions, experiences of poverty or homelessness, or learning and physical disabilities, all of which are linked to higher levels of digital exclusion.

Some interviewees also expressed that learning through experimentation is just as important as data, particularly because digital inclusion for health is an emergent field of practice.

“The data comes from the initial piloting work, I think, because this work is so innovative. And because of the way that digital keeps changing and accelerating, I don't think we have all the data and evidence yet. The answers are there, in terms of what creates the systematic inequalities we have, but that will only come from us co-creating knowledge with communities.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

In practice: Using data to improve community health and wellbeingback to top

One local authority is working with their integrated care board to improve the health and wellbeing of residents, by providing equitable access to technology-enabled remote blood pressure monitoring.

The project came about to help meet the needs of a high proportion of residents with long-term conditions including hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, and COPD.

The programme is funded by the integrated care board, with additional financial support to purchase blood pressure monitors from NHS England. The monitors are distributed to patients and GP practices, helping reduce any health inequalities for people who may not be able to purchase a monitor of their own.

The programme team has adopted a data-led approach to risk stratification and population segmentation to enable and scale its services, drawing on a variety of data sources including primary, community, mental health, social care, and acute data. The same data tools have now been adopted by primary care networks within the integrated care board area.

This work has been supported by building skills and support for digital inclusion, including digital champions, data ambassadors, digital health advisors and care coordinators. Working with development and workforce teams, the programme team has been able to fund local digital fellowships and create both communities of practice and networks for professions including nursing, pharmacy, and allied health.

To date, more than 31,000 blood pressure readings have been recorded by more than 450 patients since the project fully launched in March 2022. Early data suggests this work has reduced the number of GP visits and improved management of a patient’s condition through access to diagnostic blood pressure readings.

Using data and peer learning to shape practiceback to top

Some interviewees spoke about the value of learning from others to shape their approach to digital inclusion for health. For example, some have directly replicated models that have been successful elsewhere, adapting as required to their own local context.

Where they have been able to, local authorities feel that learning from others has helped to accelerate their progress and impact, particularly in relation to activities delivered in partnership with integrated care boards. However, they observed that there are currently few opportunities for this type of focused learning and would welcome more space for discussion and reflection with both local authority and primary care colleagues.

“I'm sure there's lots of really good stuff happening across the country, why would you want to reinvent the wheel if something really good is happening elsewhere? Why not share it and we can all benefit from it?”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

The challenges of reporting shared outcomes between partnersback to top

Local authority interviewees told us that while their desired outcomes for digital inclusion projects are very similar to their counterparts in primary care, it can be difficult to identify shared success measures due to differing priorities and reporting requirements. More broadly, they are grappling with the challenges of meeting the reporting expectations of their wider stakeholders.

“One of the big challenges is, ‘What do you measure? What do you report on? What's important?’ That doesn't always tally.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“There's resource going in, so there needs to be success flowing back into our communities. Otherwise, we won’t win over the support of either our communities or councillors.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Other local authority leaders and managers find it particularly challenging to report on outcomes because it is difficult to directly attribute health impacts to digital inclusion interventions.

“The attribution of the impact of digital inclusion is very, very, very difficult to trace, especially when you're thinking about health outcomes… how to monetise the impact of prevention.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“It’s really hard to ask, ‘so how does this investment reduce health inequalities?’ It's much more about correlation than it is causation… that's an interesting conversation we are navigating alongside health. We can't just say that digitally connecting people will equal X. It's much more holistic.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Local authority interviewees perceive that building a shared understanding with primary care partners about the nuances of reporting on outcomes, and a commitment to developing holistic, person-centred outcome measures, are important in helping to address some of these obstacles. However, they recognise that this is a significant challenge.

Data and learning: Top tips for getting startedback to top

- Start with the person: Consider the ‘user journey’ for people who are digitally excluded – what are their barriers when it comes to accessing support with their health? Focusing on individual experiences of people and communities, and the specific challenges they face, will make it easier for you to translate your learning into action.

- Build on existing insights: Use a variety of tools to build an understanding of which people and communities are at highest risk of digital exclusion. The Digital Exclusion Risk Index (DERI) for England, Scotland and Wales is a good place to start, and you can gain further insights by talking to partners and people who have lived experience.

- Use your learning to continuously improve: Get comfortable with ‘learning by doing’. Especially with emerging partnerships, you won’t have all the answers on day one. By making space for experimentation, trial and error, you can adapt and improve as you go.

Data and learning: A senior leadership perspectiveback to top

- Build an evidence base: Senior leaders should leverage data to create a solid evidence base that highlights the nature and extent of digital exclusion. You can use this to engage with external partners, make a compelling case for digital inclusion efforts and foster collaboration across sectors.

- Use data to inform strategic interventions: Data-driven decisions help leaders focus on areas with the greatest potential for impact. With the right data, you can strategically target interventions, ensure your resources are allocated effectively, and deliver digital inclusion initiatives that are responsive to community needs.

- Continuously assess and measure outcomes: To ensure that digital inclusion initiatives are delivering value for public investment, leaders must continuously assess the outcomes of their efforts. Use data strategically to track your progress, measure your impact, and communicate it to others.

Combined local knowledgeback to top

The local authority leaders and managers we interviewed recognise that primary care providers bring community expertise that is complementary to their own. Drawing on this combined knowledge, alongside the specialist expertise of VCSE organisations, is vital to promote digital inclusion for health.

Interviewees consider themselves to be well placed to understand the needs of their communities because local authorities provide a range of services that contribute to health and wellbeing, such as housing, education and employment. They perceive that primary care partners add significant value to this due to their community footprint, and the trusted relationships that GPs and other health professionals have with patients who are at risk of digital exclusion.

“Some people would never have had the confidence to go walk into a library and say, ‘I've just been given this tablet, and I don't really know how to use it, can you help me, please?’ There are some people who are never ever going to do that, but pretty much everybody goes to their GP [surgery]. We felt that if we could work with GP [surgeries], we could reach more people and reach the people who needed our help the most.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

VCSEs are perceived to bring different, specialist expertise, which is critical to help reach the most digitally excluded groups. Some of the examples given include charities and social enterprises, faith groups, food banks and social prescribers. Their expertise is perceived to play a range of important roles, including: providing physical space to engage with people who are already using and accessing services; supporting local authorities and primary care providers to target their activities effectively, by helping to identify priority groups and listening to the voices of people with lived experience of digital inclusion; and promoting engagement with digital inclusion projects due to their knowledge of the communities and groups they are working with.

“For example, sometimes we might talk about English as a second language (ESOL) and decide that one of our priority populations is transient communities. But under transient communities is a really broad group of communities who will have different barriers, different experiences. We need to have so much more of that localised learning.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“There is help and support through social prescribing. I've shared some information with the GP practice managers to pass on to their social prescribers because there are referral routes that can be followed to help patients who the social prescribers are seeing. For example, to signpost them to a digital champion in their local library, or to loan equipment.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

Local authority interviewees emphasised that while VCSE organisations play a pivotal role, they cannot do so without appropriate resources. Therefore, several local authorities are prioritising capacity building and co-creation alongside the VCSE sector.

“I think it's important to understand that the third sector plays a big role in digital inclusion, it's not just about the local authority and health.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

“What we're trying to build now, is capacity [in the voluntary sector]. For example, we had some funding to look at loneliness and isolation for older adults… we flipped it a little bit and said, ‘right, here's a pot of money, you can bid for funding for innovative projects that help to reduce loneliness and isolation. What came back was absolutely mind blowing… as big organisations, we [local authorities and primary care] need to say, ‘actually, we don’t need to own all of this’. And our role is to take that learning and actually make service change on the back of that.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

“The model that we've developed is that when we get that funding, we will almost always place those digital inclusion roles in third sector organisations… The voluntary sector is often where the expertise already sits. Those organisations know the people that they're working with and supporting… We are big advocates for is embedding digital inclusion within the existing services that people are already using and accessing.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

In practice: Building capacity within the voluntary sectorback to top

One local authority that has adopted a community-based approach to digital inclusion for health is prioritising capacity building within the VCSE sector. Alongside primary care partners, they have identified three priority areas of focus: digital inclusion among older adults; digital inclusion among people experiencing homelessness; and digital inclusion among people who speak English as a second language.

The partnership is based on a shared understanding that VCSE organisations are uniquely placed to understand the needs of the communities they work with, and often hold many of the solutions to digital exclusion, but lack the capacity to address health inequalities using digital approaches.

“I don't think we are that much different to other local authorities, in that the voluntary sector is increasingly fragile in terms of their funding… as we deliver a community-based model, I'm really cautious of putting this on all of our [VCSE] organisations to deliver.”

(Local Authority Digital Inclusion Lead)

To address this, the local authority is playing a convening role, to bring together a number of different partners including primary care, to develop and secure funding for larger, more sustainable projects. To date, this approach has enabled the local authority to test and pilot connectivity projects within temporary and supported accommodation, supported by independent evaluation to understand their wider health and social impacts. The success of this pilot will enable the partnership to roll out the programme to up to 200 households within the local authority area.

“The team do a lot of work through the [VCSE] sector… it's great because we can actually help those organisations through the provision of devices, skills, and by hooking them into industry to draw on business funding. We can join the dots.”

(Local Authority Senior Leader)

Combined local knowledge: Top tips for getting startedback to top

- Engage VCSE organisations: Support and encourage the involvement of VCSE organisations, as they have vital connections to communities and can help to promote digital inclusion among people and communities who might otherwise be excluded.

- Collaborate with businesses: Involve businesses in your digital inclusion efforts. Explore ways to leverage their resources, technologies, and expertise to enhance access to digital inclusion for health services.

- Build place-based networks: Foster networks in your local area that bring together people and organisations working on digital exclusion. Share insights, best practice, and collaborate on common challenges to drive progress.

Combined local knowledge: Top tips for senior leadersback to top

- Support VCSE organisations to deliver: VCSE organisations bring invaluable assets to your partnerships, but they need adequate resources to do so effectively. Consider ways to build capacity within these organisations, to ensure your approach is sustainable in the long term.

- Tap into the expertise of your wider network: Consider how existing strategic partnerships and networks can add value to your work – for example, businesses, schools and universities. Many of these partners possess valuable insights, knowledge, and skills that can support your collaboration efforts.

Skills, capabilities and attributes for successful partnership workingback to top

Local authority leaders and managers identified a range of skills, capabilities and attributes that they and primary care partners require to work successfully together.

While some interviewees said they already possess (or have developed) these qualities, others were less confident about working in partnership. This is particularly true of local authorities at an earlier stage of working in partnership with primary care, who generally had less experience of operating within a health context.

There is a high degree of overlap between the qualities required of digital inclusion programme leads and senior leaders, reflecting the collaborative nature of many digital inclusion initiatives. However, as highlighted in Figure 2, local authority leaders and managers alike considered that some qualities are particularly important for senior leaders (for example, setting the vision and influencing others) and others for programme leads (for example, securing funding and effectively using data).

The ability to build trusted relationships with partners and communities was considered equally important for both programme leads and senior leaders, underpinned by a personal commitment to tackling digital inclusion.

Show image description Hide image description

A diagram showing the skills, capabilities and attributes for sucessful partnership working for senior leaders and programme leads. Arrow at the top, bold white text from left to right reads: "Senior Leadership. Programme Leadership." Below in five different circles, which are different shades of blue and green, white text reads: "A strategic outcomes-focused approach. Ability to champion digital inclusion and influence beyond organisational boundaries. Ability to develop trusted relationships with partners and comminities. Expertise in working collaboratively to secure funding and resources. Expertise in using, combining and interpreting different forms of data." In navy blue rectangle below, bold white text reads: "Personal commitment to tackling digital exclusion."

| Quality | Description |

|---|---|

| A strategic, outcomes-focused approach |

Interviewees emphasised the importance of having the skills to collaborate effectively with primary care partners in building a shared vision for digital inclusion and identifying clear outcomes. They highlighted that the ability to engage in constructive challenge and navigate setbacks is essential, fostering a mindset that encourages resilience and adaptability. Key attributes include the ability to maintain a broader perspective, continuously reassess progress, and realign efforts with the vision, ensuring that all partners stay focused and motivated despite challenges. |

| An ability to work flexibly and influence beyond organisational boundaries |

Interviewees considered that an ability to work flexibly and influence beyond organisational boundaries is important to achieve success. This is important given the wide-ranging nature of local authority and primary care services, involving many different stakeholders and with priorities that may change regularly in response to external pressures. Local authorities who have more emergent partnerships with primary care highlighted that they would welcome support to better understand organisational structures within primary care (and how this relates to other parts of the healthcare system). |

| Ability to develop trusted relationships with partners and communities |

Interviewees told us that the most important (and first) element of building a relationship with primary care is developing mutual trust and building an in-depth understanding of each other’s perspectives. Recognising that local authorities and primary care partners might have different starting points for working in partnership, local authorities spoke about the importance of being able to find shared language to communicate their different perspectives and ways of working. They felt this is particularly important when it comes to communicating with people and communities, as local authorities sometimes find it difficult to support people when they themselves are unfamiliar with the tools and or terminology used by primary care services. |

| Expertise in working collaboratively to secure funding and resources |