Scaling solutions to data poverty in the UK

Data Poverty Lab Fellow Kat Dixon explores what data poverty is, how it manifests in people's daily lives, current solutions available & how we can collectively scale these solutions.

Watch, download or read “Local communities and the internet ecosystem: Scaling solutions to data poverty in the UK“

A version of this report is available to download on the right of this article. Alternatively, you can watch the launch of the report below, or read the full text-version on this page.

What can we do, together, to make data poverty a thing of the past?

Foreword

The Data Poverty Lab is imagining a world where everyone has the internet access they need. In this world, anyone in the UK can pick up a phone, tablet or laptop and be connected. They don’t start a video call with their GP and find out drops out mid-conversation. They don’t walk to a friend’s house to apply for jobs. They don’t stand next to a chicken shop to check maps using the free WiFi. They have access to essential UK services. They connect with family and friends. They participate and thrive in our modern world.

This report is a provocation. It offers a snapshot of current and emergent ways of tackling data poverty, their pros and cons, and ways to scale solutions within the complex ecosystem of internet access.

There are many ways our future could unfold. We face a critical moment in the wake of a global pandemic and the midst of economic challenges, where we can shape the future horizon of digital equity in the UK.

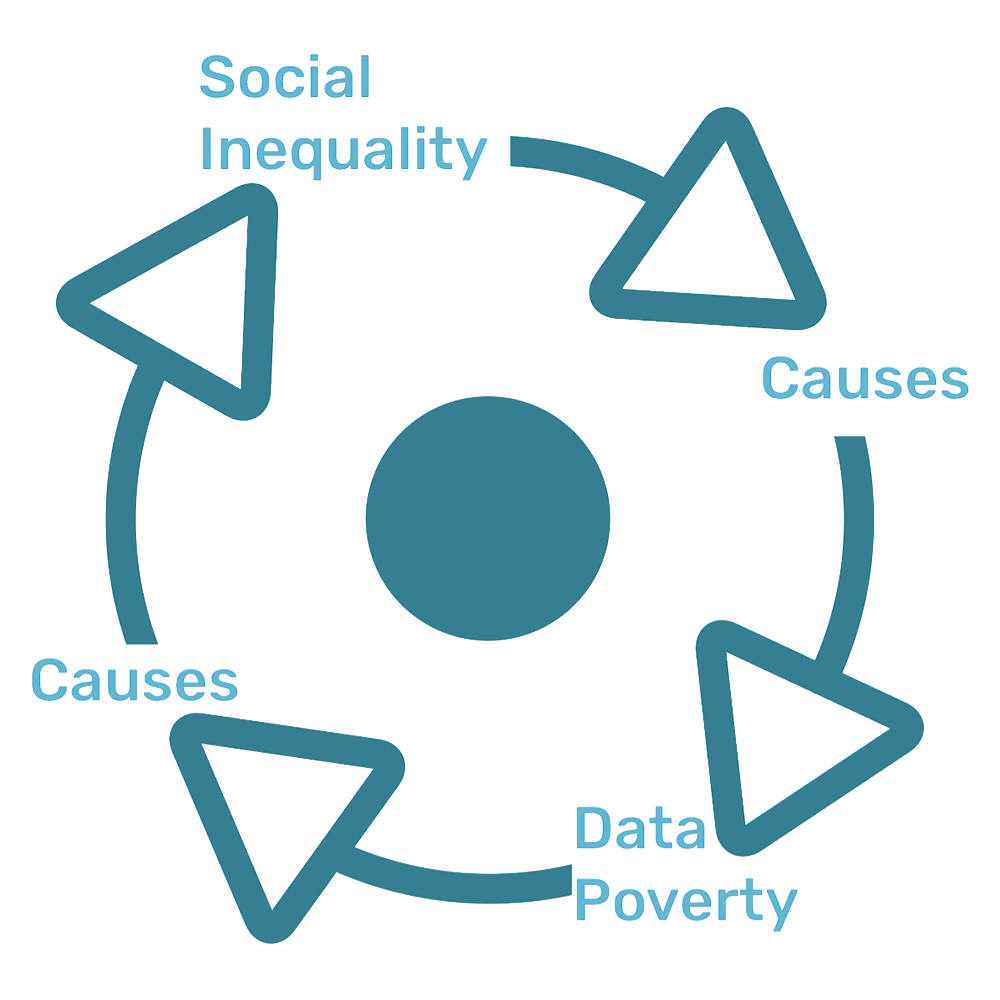

Interventions which tackle data poverty will help level up UK society. Data poverty is best understood as a cause and a consequence of social inequality. It is my hope these recommendations to scale solutions will mean more UK citizens get the internet access they need.

I set out to find place-based pioneers and ways to scale community-led solutions. What became abundantly clear is that the local cannot be disconnected from the national. In this complex ecosystem, community work is inextricably tied to a national and international ecosystem.

Across the four nations, I found brilliant examples of determined yet modest community leadership. From foodbank workers giving out SIM cards to start-ups developing new technologies, there are incredible pockets of determined people making change happen across the UK. The case studies throughout this report give a glimmer of what goes on behind the scenes.

I also found huge amounts of goodwill and collaboration. Telecommunications companies teamed up with housing associations; Local Authority teams joined forces with charities and social enterprises. This is a space full of energy, vibrancy and urgency.

Communities know their local people better than anyone. As we build towards a more equitable and inclusive digital future, we cannot rely on communities finding workarounds to gaps in national policy and provision. We must create locally-driven, nationally supported solutions. We must build funding, structural support and a coherent national strategy.

This is a journey towards a new horizon. Fifty years ago, no one could have predicted what a smart phone might mean to daily lives. We can’t know the future but we can decide, right now, to bring everyone with us.

UK life exists online. Over two million people are disconnected from the internet, and so our society. We must tackle data poverty with the urgency it demands, to build a world where everyone has the internet access they need.

Executive summary

The Data Poverty Lab is run by Good Things Foundation, a national digital inclusion charity. They commissioned this report – one of three fellowships – to explore solutions to data poverty across the UK. This research takes its North Star from Good Things Foundation’s 2022-25 strategy; imagining a world where everyone has the internet access they need.

Aim of report

This research explores what data poverty is, how it manifests in the daily lives of people living in the UK, the current solutions available and how we can collectively scale these solutions across government, business, the third sector and communities across the UK.

This report offers a pragmatic approach to comparing interventions and some practical next steps to tackling data poverty. It offers a few paving slabs on a long pathway to building a more equitable digital future. It is a provocation for charity workers, policymakers, Local Authority teams, academics and beyond to consider our next steps in taking collective action. What can we do, together, to make data poverty a thing of the past?

Methodology

The findings in this report are drawn from interviews with more than 85 individuals, spanning frontline workers, people with lived experience of data poverty, telecommunications workers, policy experts, politicians, trade industry representatives, academics, IT experts and digital inclusion experts. Alongside desktop research, this forms a snapshot of data poverty as it appeared in the Summer of 2022.

Throughout the report, you will find case studies from different parts of the UK and quotes. These illustrate both the reality of living with data poverty and how communities and organisations are building solutions. I recommend browsing the quotes and case studies of this report; they breathe life into a complex subject.

Structure

Part 1 explores what data poverty is and why it matters. Part 2 looks at existing solutions, their advantages and disadvantages and how they might be scaled. Part 3 considers the wider ecosystem and how we can build a future-proof approach to digital inclusion and equity.

Findings and insights

Five key findings emerged from this research:

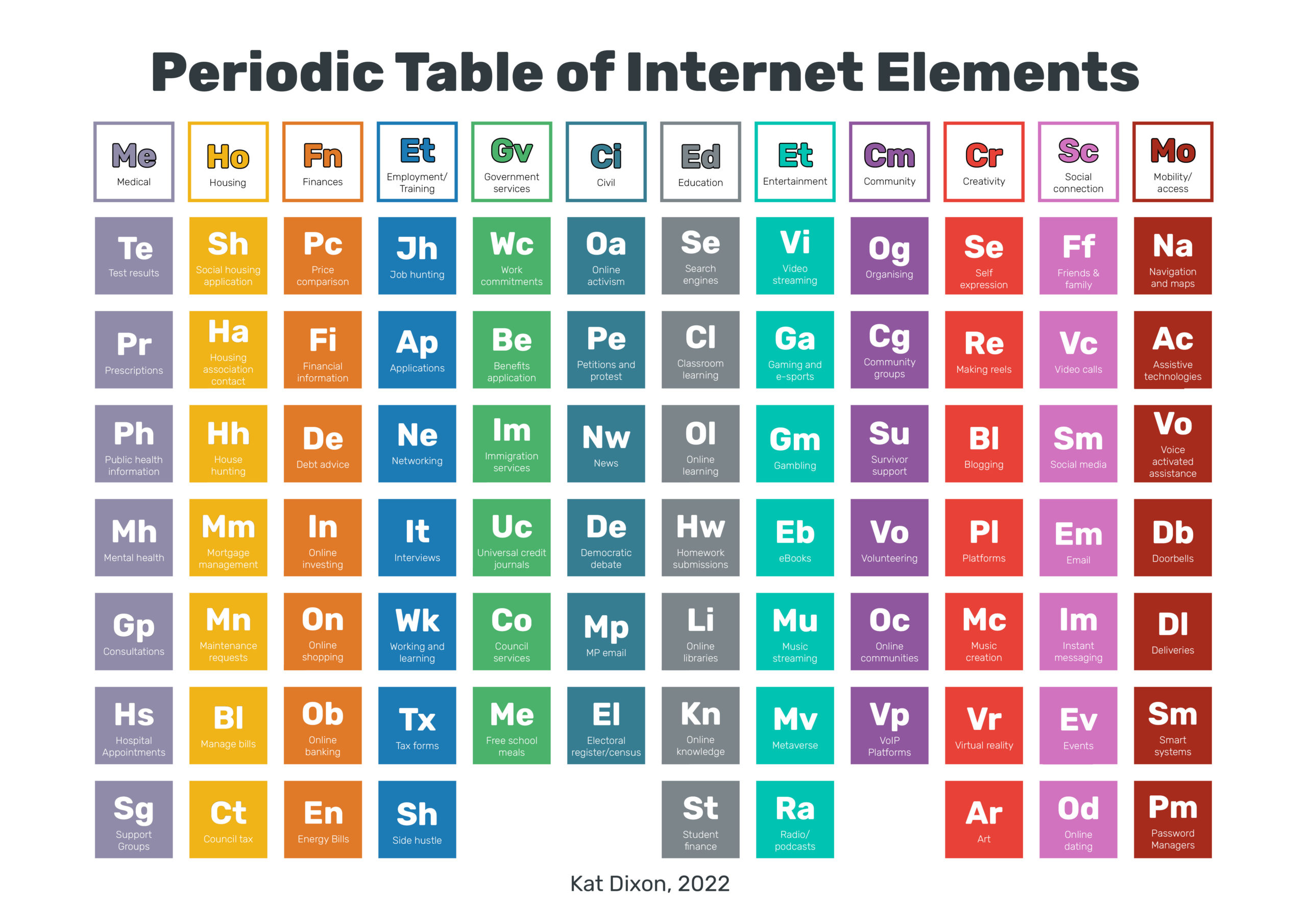

- Data poverty in the UK excludes people from access to essential services and participating in UK society. A key output of this research was The Periodic Table of Internet Elements, a graphic which lays out different elements of how the internet is used by UK citizens. This graphic captures what has long felt intuitive; that internet access is essential, a human right and spans essential needs, identity, self-expression and connection. If we are not online in today’s world, we are excluded from UK society.

- Data poverty disproportionately affects people who already face social inequality and deepens their disadvantage. UK citizens who have experience of being in care, claim benefits, are refugees, have a disability or long-term illness, are fleeing domestic violence, or face other forms of social disadvantage are more likely to face data poverty. Lack of good internet access makes their situation worse. In times of crisis or cycles of struggle, access to the internet is all the more vital.

- Affordability and accessibility is a central challenge. The cost of living crisis and the impending recession is forcing families to choose between rent, bills, food and internet. Affordability is key, but it is closely accompanied by accessibility. Citizens are not always aware of cheaper options, nor do they feel empowered to access them, due to fear of being disconnected, accessibility barriers and the complexity of switching when life is already a tangle of complicated threads.

- Strong solutions to data poverty exist in the UK and some are ripe for scaling. This research details nine solutions to data poverty, offering their pros and cons and how they might be scaled. It offers a framework for comparing solutions, specifically focused on the needs of individuals disproportionately affected by data poverty. This framework can help us understand solutions now and in the future, as technology evolves.

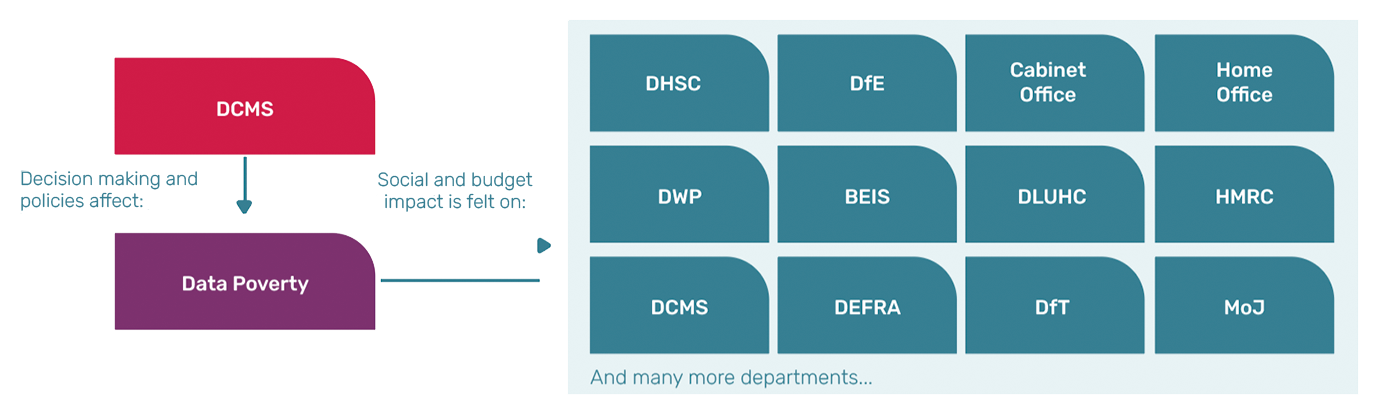

- Community-led solutions can only be understood and scaled within the context of a wider ecosystem. The ecosystem of internet access is complex: telecommunications companies, government at all levels (local, regional and national and central Government), regulation, global investment, local communities, philanthropy and the individual intersect to create access to what has become a human right. The internet is now equivalent to a utility, a pipeline to essential state-delivered services, like the NHS. Community interventions are vitally important, but they are liberated or hindered by the wider conditions. To scale up community-led solutions, we have to look at the wider ecosystem and conditions for a sustainable future.

Recommendations

This report offers three overarching recommendations:

- Focus collective effort on scaling solutions suitably for reaching people who need internet access the most. The three solutions identified as most ripe for scaling are:

- WiFi in a box: this relatively cheap technology uses mobile signal to provide home WiFi. This is a quick fix to get people and households internet access now. It is more suitable and sustainable than other quick-fix solutions. The case studies featured in this report show how.

- Social tariffs: affordable tariffs for people claiming benefits in the UK is a core, scalable solution. Work must be done collaboratively with industry to scale up adoption. This could be via automatic enrolment, switching support, awareness raising and other methods. Central Government subsidy will be important to make this truly affordable to everyone who needs access to essential services.

- Community fibre providers: are organisations who put community needs as a central mission of their work. Altnets who advocate on behalf of their communities will be crucial in getting rural areas the fibre infrastructure needed for long-term connectivity. The market conditions, regulation and subsidies must continue to support these organisations.

- Continue to build a collaborative effort across the ecosystem, harnessing goodwill to develop appropriate regulation and government support. Getting everyone the internet access they need has to be a collective effort. The UK infrastructure backbone comes largely from private investment. There is much goodwill amongst telecommunications companies to address data poverty, but they have a responsibility to make a financial return to keep that investment coming. The UK needs this investment, to keep up with future infrastructure needs.Market forces have helped us bring the overall cost of internet down; it is relatively cheap compared to many other countries. In tackling data poverty – those being left behind by this system – regulation and subsidy must work collaboratively with industry to harness market forces and find a delicate balance that services all UK citizens. This will help us move into the future and bring everyone with us.

- Politicians and public policy makers need raise the level of prioritisation of digital inclusion. Data poverty is inextricably tied to digital skills, devices and confidence. It affects the success of every government department – health, work, energy, enterprise, housing, education, benefits, migration, tax – at every level of government. All of these elements of our lives and of government require good internet access in the modern age. The impact and budgetary pain of data poverty is felt by all departments, but the responsibility is not shared by all. This report recommends:

- A new and unifying Digital Inclusion Strategy from Central Government, with buy in across government departments

- Manifesto commitments to prioritising digital inclusion

- Independent research which quantifies the productivity and economic losses of data poverty

Limitations and further study

This report offers a snapshot of data poverty and its solutions as it was in the Summer of 2022. Technology evolves ever faster; some solutions were not selected as ripe for scaling due to issues of privacy and net neutrality. A person who finds internet unaffordable or who struggles to access internet should never pay for that access with their privacy or rights. In future, evolutions in implementation or technology might address these issues, in which case these reservations will be rightfully out of date.

The Periodic Table of Internet Elements and the overview of solutions are not exhaustive. Social inequalities and social barriers are not homogenous; the different people I spent time with had vastly different experiences. What is attempted here is to bring together commonalities in experience which can help guide decision makers and passionate people tackling this issue make challenging choices. More research is needed on the impact at a larger scale, the variety of experience in urban, coastal and rural areas, the intersectional nature of inequalities and the environmental impact of these solutions.

Conclusion

Lack of good access to the internet is both a cause and a consequence of social inequality. In the UK, it affects access to essential services, our ability to express ourselves, how we connect with others and participation in society. The scaleable solutions identified here offer a next step towards a future horizon, where data poverty is a thing of the past. This research is inspired by tangible examples of how collective action across the four nations is making progress; the case studies here show that we are already finding a way forward. The challenge is how we bring everyone with us into that inclusive digital future.

Introduction

Aim of report

The Data Poverty Lab is a collaboration between Good Things Foundation and Nominet, set up in 2021 to find sustainable solutions to data poverty. This report is one of three fellowships and explores future-facing solutions to data poverty.

How to read this report

A quick guide for different audiences

Charity workers, social enterprises, community advocates, philanthropic funders, you might be most interested in:

- A quick graphic on why the internet is essential

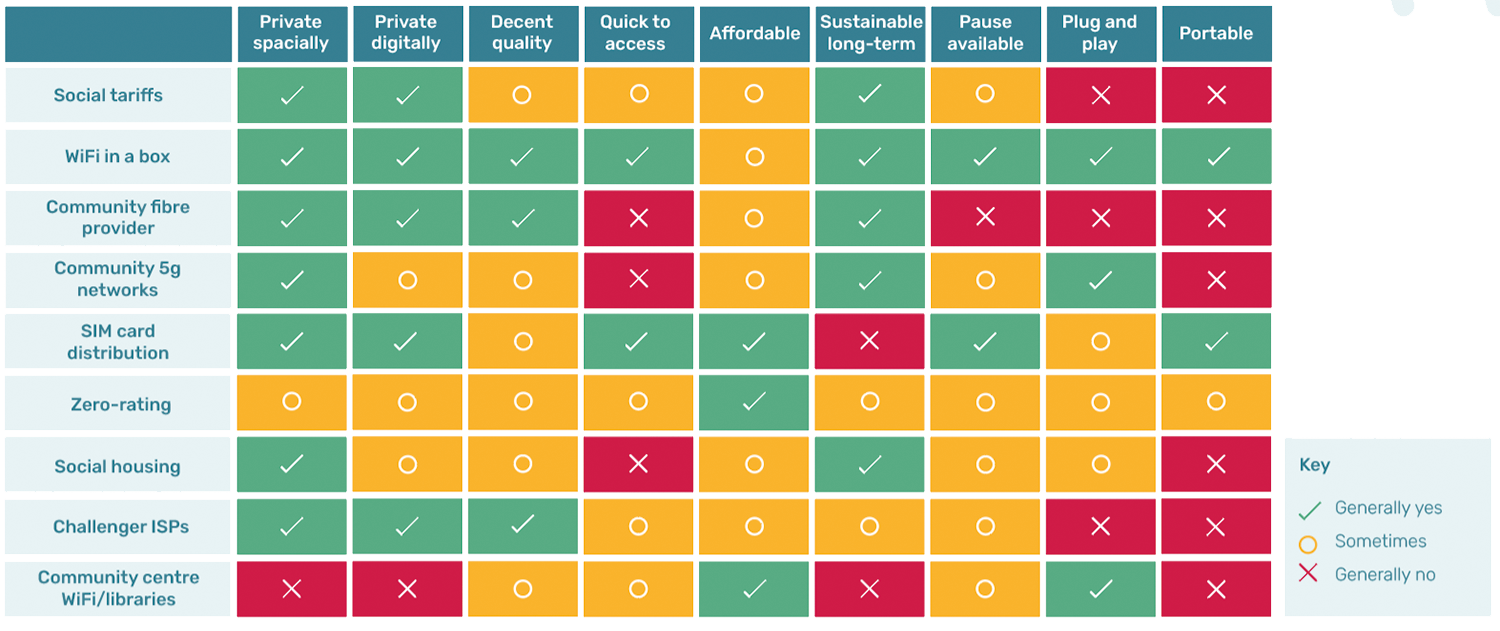

- This matrix which compares different ways to get people online

- The insights section capturing lived experience

- My top recommendation for getting local people online is WiFi in a box

Policymakers, politicians, telecommunications colleagues, regulators, civil servants, you might be most interested in:

- A quick graphic on why the internet is essential

- This matrix which compares different ways to get people online

- Ways to think about social tariffs

- Part 3: Towards a healthy ecosystem for the future

Local Authority workers, you might be most interested in:

- A quick graphic on why the internet is essential

- This matrix which compares different ways to get people online

- My top recommendation for getting local people online is WiFi in a box

- This section on Local Authorities

Researchers, academics, you might be most interested in:

Part 1: What Is Data Poverty and Why Does It Matter?

This report takes its North Star from Good Things Foundation’s 2022-25 strategy: that everyone has the internet access they need.

Data poverty in the UK is no longer about being online or offline. It is about whether the internet that reaches you reaches your needs. Data poverty in the UK is more likely to be experienced as internet that is too slow, or drops out, or internet you can’t afford.

Data poverty in the UK is rarely experienced in the way that data-rich people imagine. Data poverty can be an older person who’s never opened a laptop. But it’s more likely to be a 14-year-old waiting for a homework page to load because they are sharing a connection with two siblings. Or a job seeker running out of data as they navigate to a job interview. Or a young mum moving between McDonalds and a chicken shop to get free WiFi to check on her kids.

Nesta defined data poverty in 2020 as “those individuals, households or communities who cannot afford sufficient, private and secure mobile or broadband data to meet their essential needs”.1

But what does essential mean in today’s world?

Work by the Nuffield Foundation with Loughborough University and the University of Liverpool on a Minimum Digital Living Standard 2 (MDLS) is working towards providing a benchmark of what devices and data connectivity qualify as a minimum standard of living. The Welsh Government is also working towards an MDLS.3

Their definition goes beyond the basic: “A minimum digital standard of living includes, but is more than, having accessible internet, adequate equipment, and the skills, knowledge and support people need. It is about being able to communicate, connect and engage with opportunities safely and with confidence.”4

The Data Poverty All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG)’s State of the Nation report calls for an agreed definition of data poverty and a mandate for the Office for National Statistics to collect data.5 This will be key for understanding our baseline is more depth and measuring progress. This report uses Nesta’s as a working definition.

Why does data poverty matter? A Periodic Table of Internet Elements

UK citizens need the internet to access essential services and participate in society.

Internet access is elemental to UK living. Our lives exist in a fluid mix of online and offline experiences, spanning medical, housing, financial, employment, education, civil, government services, entertainment, community, social connection, creativity, mobility and access.

“For me, having data is as important as having stuff in the fridge for me to eat. Because I can’t operate. I can’t live day to day if I can’t connect.” Lived experience participant

This graphic represents what people in the UK use the internet for. The overall domains are split down into the elements of internet access.

Three key takeaways from the table of elements:

1. In the UK, many of these elements partially exist online. Anyone who doesn’t have internet access is cut off from real-world access too.

“I can’t walk into my doctors if I need to prescription or something, I have to go online if I need to renew.” Lived experience participant

2. Many essential services are digital first; they are provided online as the default access option. This means the cost-barrier of internet access can prevent vital access to essential services.

“If it costs you £40 a month to get access to the NHS, the NHS isn’t free anymore” – Simeon Yates, digital poverty expert

3. Elements mean different things to different people; a video doorbell offers convenience to an office worker, independence to a wheelchair user, and safety to a woman fleeing domestic violence.

“[The internet means] freedom to do things you really need. We take for granted what we do online. It can be very insignificant to some people, but it can be life changing for others.” Community Worker

Why do people face data poverty?

Like all subject areas of poverty – fuel poverty, food poverty, period poverty – data poverty is largely driven by poverty.6 Many people in the UK cannot afford internet.

Data poverty is linked to geography and confidence. Because of changing infrastructure, it is possible to be both financially, socially and culturally wealthy, but face data poverty. It is also possible to live amongst the most technologically advanced infrastructure in the world and be disconnected.

Affordability

In 2021, around 2 million households were experiencing affordability issues with their broadband or smartphone. For people who aren’t online, 19% say cost is the main reason.7

Telecoms bills are becoming unaffordable for many. The cost of living crisis is forcing families to make impossible decisions, with 5.7 million UK households in April 2022 struggling to pay their mobile, landline and broadband bills.8 The lowest earners spend almost double their proportion of income on telecoms than the highest earners.9 The poverty premium means that Pay As You Go customers pay comparatively more for their internet access.10

Geography

Urban areas have better broadband and mobile coverage than rural areas, and better speeds. Only 83% of rural areas in the UK have access to superfast broadband (30Mbps) compared to 96% of urban areas.11

To address limited rural access, the UK Universal Service Obligation (USO) for broadband was introduced in 2020. This creates a baseline expectation that all internet Service Providers (ISPs) must offer everyone a service for a minimum of £48.90, no matter where they live. Although this prevents ISPs from charging very high fees for connecting rurally isolated individuals, this price is unaffordable for many.

Mobile coverage is not as good in rural areas than urban areas. Only 81% of UK premises has 4G data coverage12 and 4% of UK landmass has no good mobile signal at all (called ‘not-spots’).13

The UK government’s manifesto commitment is to deliver nationwide Gigabit broadband by 2025. This target was revised in November 2020 to a minimum of 85% of premises by 2025, and in February 2022 this was revised to gigabit broadband coverage ‘nationwide-by-2030’ (99%).14

Confidence

Ofcom data shows that the top reasons for not going online are perceived lack of need or interest (47%) or that it was too complicated (31%). Motivation, education and confidence are closely tied together. Many individuals express lack of interest, but when shown the benefits demonstrate increased engagement.15

“Once they start it allows them to feel a bit more at ease with everything, they don’t feel as kind of intimidated by the internet. They’ve realised it’s actually fairly easy.” Community Worker

Social inequality

Data poverty is best understood as a cause and a consequence of social inequality.16 Data poverty is felt acutely by people facing a form of social disadvantage, who may not have the finances, skills, situation or social capital to get good internet access.

People who face a form of social disadvantage use government services more than the average citizen17 and therefore access is more critical to them. Lack of adequate internet access fuels these challenges, reducing access to essential services in health, housing, work, education, civic participation, social connection and beyond.

Interventions which tackle data poverty take a step closer to breaking cycles of social inequality. Access to services and support improves lives. It is circular; one informs and amplifies the other.

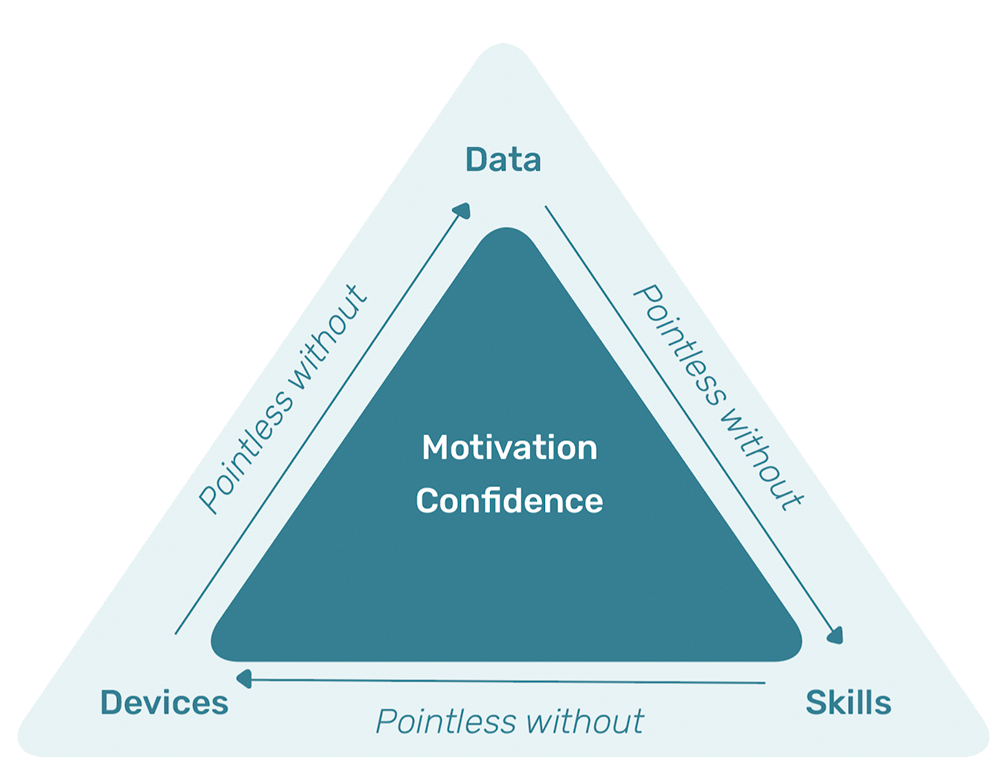

The pointless triangle

Data poverty exists within wider digital exclusion and inequity. Devices, data and skills are pointless without each other. Individuals need the confidence and support to safely conduct their lives online.

All recommendations in this report are framed in this wider context: any initiative which tackles data poverty must address digital inclusion and equity; access to devices, data and skills, and the ability to use the internet confidently and safely.

Who is affected by data poverty?

Some groups are disproportionately more likely to have no or poor internet access:

- Low earners are less likely to have home internet. 51% of households earning £6,000-10,000 had home internet access compared to 99% of households with an income over £40,001.18

- People in lower socio-economic groups (DE) are more likely not to have internet at home; 14% compared to 2% in higher socio-economic groups, (AB).19

- Benefit claimants are less likely to be digitally engaged20 and households on Universal Credit are nine times more likely to be behind on their broadband bills.21

- People living in rural areas are more likely to have limited access. 9% of rural properties cannot receive a decent home broadband connection (fixed line); this is only 1% in urban properties, and 2% in the UK overall.22 Around 0.1% of UK properties can’t get access to decent fixed broadband (10Mbps) or 4G, meaning they are effectively cut off from the online world at home.23

- People age 65+ are more likely not to have internet access; 1 in 5 compared to just 1% of 18-34 year olds.

- People with a disability are less likely to be internet users.24 Notably, when people with a disability are online, they are 27% more likely to say the internet makes them feel less alone.25

- Young people struggle with affordability; 18-34 year olds are three times more likely to be behind on their broadband bill. 26

- Ethnic minority groups: Some initial links between digital exclusion and people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups have been established.27 The UK Digital Poverty Evidence Review 2022 calls on larger sample sizes to understand intersectionality across ethnicities, socio-economic status, age, education, income, geography and beyond.28

- Data is limited on internet access for refugees, asylum seekers, care leavers and people facing homelessness. Reports from frontline workers suggest access is limited to these groups, especially due to financial instability and having unstable accommodation.

A note on approach and methodology

This research is non-exhaustive, and inevitably there will be gaps. It was conducted primarily over three months, using a combination of literature review and qualitative research methods. I spoke with over 85 individuals, including frontline workers, people with lived experience of data poverty, telecommunications workers, policy experts and politicians, trade industry representatives, academics, IT experts and digital inclusion experts.

A key gap in this research is the environmental impact of these solutions. Although the solutions identified hold in mind the implications of increased data consumption and data storage, the environmental footprint of data is not explicitly explored. Retrospectively, this is an omission. 29 Although developments in data storage technology may find ways to mitigate these risks, any future work on data poverty and sustainable solutions must be environmentally-minded.

Key insights from research

Internet as a Human Right

The internet was frequently described as a human right. Participants described how ‘everything’ is online, including many things which offer individuals the chance to live independently and with dignity.

“Having the internet and data is essentially a human right. ”Lived experience participant

“[The internet is] a basic human right that we have these days. To be independent to be able to look after yourself. How can you look after yourself without all the information and you can’t get access to it?” Community worker

“It’s like everybody’s third arm now isn’t it, the internet. And if you’ve lost that third arm, what do you do?” Lived experience participant

Essential Services Exist Online

Access to essential services are frequently digital first. Participants expressed frustration that essential needs are online, and there is not always help to access them.

“If I walk into my local bank I can’t get to see anybody. Actually there’s no people in there. It’s like the Marie Celeste and if you do dare find a person they say, oh no, oh no, you’ve got to go online.” Lived experience participant

“If you’re forcing people into a position where they have to use these services online, then there should be an easier way of making it available for them.” Lived experience participant

Elijah*, 53, reflected that when he was homeless, he found himself discharged from addiction services. Without the data to log in, he didn’t receive electronic appointment notifications, and so was discharged:

“It was so frustrating, I’d say to them I do want the support but I haven’t got any data. It was that catch-22 cycle they would say well you’re not engaging with this and I’m saying but I haven’t got the tools to engage.” Elijah*, 53

Mental Health

Limited data is a cause of stress and anxiety. Participants frequently referenced the stress caused by managing data allowances.

“It’s like watching your electricity meter tick down. It’s another thing you have to monitor and manage.” Project manager, digital inclusion project

Janine* uses a basic Pay As You Go phone which she borrowed from a friend so she can get to job interviews. Every time she goes to a job interview, she gets anxious about how much data it’s using to navigate. She can list public WiFi spots easily: McDonalds, Thunderbird Chicken, Barclays, Wagamama’s, some gyms.

“I definitely feel anxious. I’m not good at maths so the whole 500GB or 1GB, I don’t mathematically know what that means. I just know how long it lasts.” Janine*.

Data allowances create a scarcity mindset. Scarcity mindsets in the context of financial difficulty are well documented, including their negative effects on cognitive capacity and wellbeing.30 This research suggests the experience of running out of data has a similar effect. The mental burden of monitoring usage, remembering to switch data off, finding public WiFi, and topping up just enough for peace of mind comes at a cost.

“I don’t have the luxury of being able to ramble on, because I’m conscious that the data’s ticking off all the time on a Zoom.” Lived experience participant

“I have to remember to turn off the hotspot and turn off the data when I’m not using it.” Lived experience participant

“When I’m using maps, walking around, it’s definitely unreliable and that doesn’t help my anxiety. So when I’m topping up, if I have money, I double it, just to be sure.” Lived experience participant

Further research on the link between scarcity mindset and data allowances could enable evidence-driven rationale on minimum data needs.

Access & Cost Of Living

The cost of living crisis is causing more people to choose between essentials; fuel, food, broadband and housing. Reports are arising of people choosing between feeding their children or paying for WiFi. 31

“They’ve had to choose between having data, feeding the meter or putting food on the table. In some instances, they’ve sold their phones.” Digital inclusion coordinator

Maria*, 23, describes that when she is low on funds, she chooses between heating and electricity.

“Electricity always wins. Because I need it for WiFi.” Maria*, 23

For some people, public WiFi is a lifeline. Public WiFi continues to be a way for people to access essential, elemental services. 6% of 8-25 year olds surveyed by the Digital Youth Index cite public WiFi as the main way they access the internet.32

Lee* doesn’t have data so he hops between WiFi at friends’ houses, bars, trains and eateries.

“Sometimes I get lost [without data to navigate]. Sometimes I’ll be in the middle of a [text] conversation and I have to leave the WiFi. It’s annoying to ask your friends for a hotspot.” Lee*

Charities which give out free data in databanks only work well when frontline workers are digital confident. Many charitable workers feel intimidated by technology and so cannot help the people they support to get good access.

“Some relatively small organisations are really digitally savvy and passionate about distribution. They end up distributing loads of data just because they really – I think – have technical skills to feel comfortable doing IT stuff.” Staff member, Good Things Foundation (National Databank).

Trust Is Low

Many participants expressed frustration and distrust with telecommunications companies. This was focused on mid-contract price changes or feeling persuaded into unaffordable contracts.

“I don’t trust phone companies. They’ve got it in their contracts they can change prices whenever they want.” Lived experience participant

“You get the phone and then six months later it doesn’t work properly and you’re stuck paying all this money… [the phones] aren’t built to last 24 months.” Lived experience participant

Buying Internet

Amongst UK citizens, digital confidence to buy internet is low. Many people expressed feeling left behind by technology and that it is too late for them to catch up. Surrounded by jargon, buying internet is very different to buying electricity or water.

“I think a lot of the people we came across it was an element of lack of confidence… some of the jargon, things like upload and download speed. It might confuse them a little bit and they didn’t quite grasp what it meant. So it’s just me being more of a guiding hand sort of help them through the process, really.” Digital Inclusion Officer, Monmouthshire

People feel they are being encouraged to buy internet they can’t afford. Participants report feeling manipulated by upselling and being encouraged to buy products they don’t need and can’t afford.

Janine*, 23, grew up in care. She lost her phone a couple of years ago, so she rang up her provider.

“I ended up agreeing on a price which I couldn’t really afford” but “you can be easily persuaded”. Janine*

When Janine lost her job, she fell behind on her bills, so the phone was cut off. She is now repaying £900 of debt but can’t use the phone.

Loyalty penalties are driving up the cost of internet. For broadband, the average loyalty penalty per person per year is £83 for mobile and £61.33 1 in 7 customers pay a loyalty penalty across broadband, mobile and mortgages.

Nellie* was paying £100/month for her internet provision, having been with the same provider for many years. A volunteer called her provider and negotiated this down to £35. Later, this went down further to £15 after the volunteer discovered Nellie was receiving Pension Credit, and so was eligible for a social tariff.

The onus is on customers to manage rising internet bills. Dean* is a Deliveroo driver and freelancer. During an economy drive, he realised his internet bill had increased from £30 a month to £55 month over 5 years, with no change to service. He switched provider and saved £30 a month.

Case study – Age UK, Hammersmith and Fulham

In the Internet Advice Service at Age UK Hammersmith and Fulham, digital advisors and volunteers help local people understand devices, data and sometime renegotiate contracts and get refunds. Volunteers report loyalty penalties affects older customers more:

“For the older generation, they like BT or British Gas or whatever. They’ve been secure. ‘I’ll stay with it. I’ll just pay what I owe.’ And that’s the mentality that they have and because of that loyalty, [it] actually costs them a fortune.” Internet Advice Service worker, Age UK Hammersmith and Fulham.

Workers in the service also see elderly people upsold heavily by providers. Many don’t understand what they’re buying.

“The amount of people that have gone into a [provider] shop and have been sold something is just shocking.”

Sanjeev*, in his early seventies, went into a mobile phone shop to transfer from a Pay As You Go SIM Card to a monthly deal. He left with a new mobile phone, a high priced mobile deal, a new tablet, insurance, plus fibre broadband to the house. He was told this was the best deal but was not shown the monitor to compare.

At its worst, vulnerable people are being scammed. A woman arrived at the service who had been to an internet café and charged £35 to send an email, which she later couldn’t find.

Gaps in provision

Care Homes & Care

Many care home residents lack private, meaningful internet access. The UK has around 20,000 CQC registered care homes and only 35% of them provide internet access for residents.34 Around 390,000 people live in care homes in the UK.35 Care home residents may not be demanding internet, but the benefit to them in terms of tackling social isolation, offering dignity, independence and improving wellbeing are huge.

Internet access also offers potential cost savings in medicines management and telehealth. Domiciliary care workers (who visit people’s homes) use digital devices to capture photographs (of tissue, for example), input case notes and document medicines. They need internet to do this and reports are coming in of a) workers having to use their own devices and data allowance and b) driving long distances to find signal to input their work. Interventions here could have vast implications for improve care, efficiency and cost-savings.

This evaluation of ‘Connecting residents in Scotland’s Care Homes’ details the significant positive impact of connecting care homes.36 Liverpool’s 5G Health and Social Care Testbed Project demonstrates strong evidence for cost savings and impact.37

16-18 Year Old Gap

There is a gap in home internet provision for independent 16-18 year olds. When we turn 16 in the UK, we can get married, apply for a house, leave school, get a full time job, get a passport, join the army, but buying monthly internet is difficult. Young people who live independently – especially those leaving the care system – either pay a poverty premium with Pay As You Go internet, find workarounds through their council or corporate parent, or go without. The apprenticeship incentives and work support for independent young people in this age bracket is less meaningful if internet is not available.

This post on an internet forum illustrates this challenge:

'AGE LIMIT for broadband account?' on 30-05-2022 06:28

Im due to be moving into a supported accomodation soon, and i have to source my own wifi as they dont have a residents wifi. Im 17, have sadly lost both my parents & i need wifi for college applications, college work/study, writing CVs for part time jobs, etc... Alot of wifi companies wont allow U18s which is so stressful, does [provider] allow U18s to get wifi?

Anonymous

Post on an internet forum

A complex picture: further research insights to inform solutions

People who cannot access the internet in the UK are comparatively more excluded than if they lived in a country with less internet access to the overall population.39

Citizens who are not online are not represented in population data. This influences data driven decisions, for example risk scoring in insurance. A recent example would be monitoring countrywide mobility using mobile phones during the COVID-19 pandemic.40

Privacy mechanisms can automatically exclude users; multi-factor authentication (MFA) can exclude people who cannot afford multiple devices. There have been anecdotal reports that MFA creates barriers to job hunting for those who can’t afford a phone41 and to those who are neurodivergent.42

There is a need to protect citizens’ right to be offline. The Welsh Government has made key strides in developing a digital inclusion offer, which includes a recognition that citizens have a right to be offline.43

Platforms and technology creators have a responsibility to bring accessibility and safety into design. Much of the focus of safety by design has been on children, such as the work of 5Rights Foundation44 and The Children’s Code,45 created by the Information Commissioners Office. This is important work, but if we are reaching for a truly inclusive and equitable future, platforms must embed safety and accessibility principles for excluded groups into design.

It’s a bit like if you manufacture a car, it has to have seatbelts in it now because we know that cars are a technology that can be dangerous, and they're also part of everyday life. We also know that people don't always use cars in life-protecting ways. But then we need to make sure that when we design that intervention (the seatbelt), we do that with - and not just for - a diverse range of seatbelt users.

Some evidence has shown women who wear seatbelts are more likely to suffer severe injuries or death than men who wear seatbelts, for example. So, seatbelts aren't working the same for everyone, and there might be physical, social, or other reasons for this. Those reasons need to be explored in the design process.

The same is true of the digital world. We have an obligation to make it safer because we know it can cause harm, and it's ubiquitous in everyday life. And we need to make it safer with the participation of people affected by it.

Kira Allmann

Digital inequality expert

Part 2: Mapping The Spectrum Of Existing Solutions

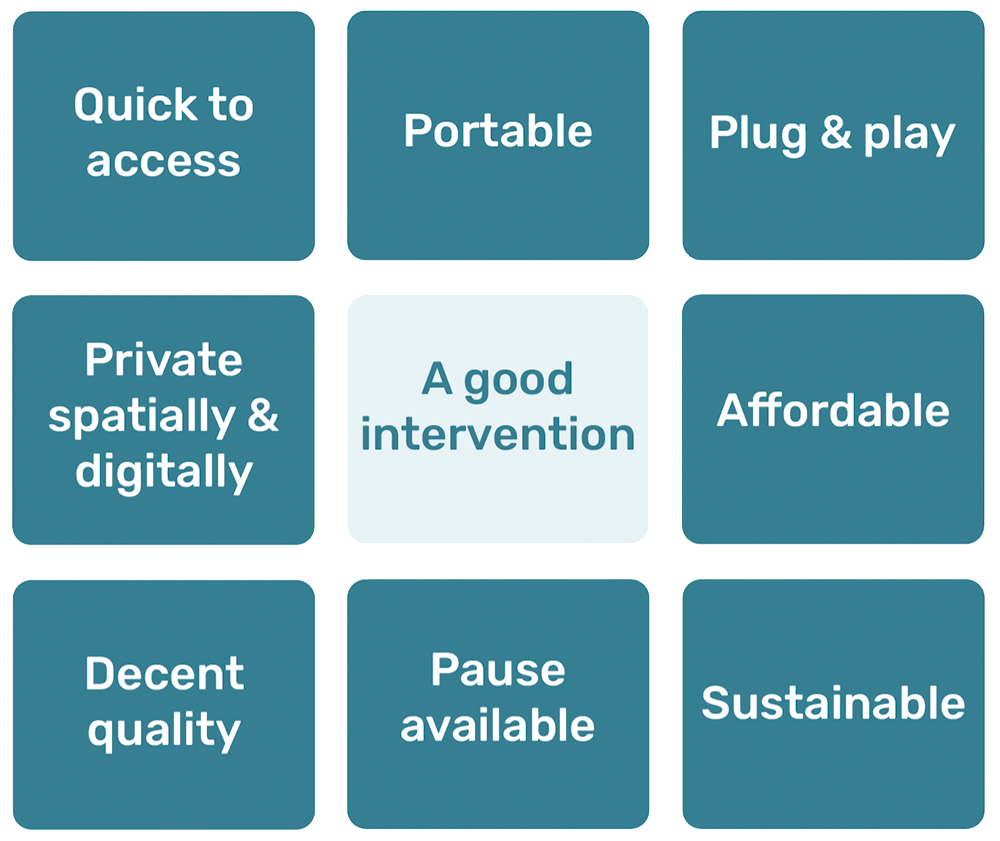

Over three months, I studied solutions which tackle data poverty. The comparison analysis in this section is non-exhaustive and offers a quick guide to initiatives which are ripe for scaling. I review these using a framework for measuring how each solution fits the needs of people disproportional affected by data poverty.

A note on frameworks

Existing frameworks which codify what makes a good internet connection:

- The CHESS framework by Good Things Foundation summarises important qualities: Cheap, Handy, Enough, Safe, Suitable.46

- The Meaningful Connectivity Framework by The Alliance for Affordable Internet considers four pillars: 4G speeds, appropriate devices, unlimited broadband and daily use, as a guiding light for assessing connectivity, mainly in developing countries.47

- The Corresponding Fields model by Ellen J Helsper considers digital inequalities in the wider context of social inequalities. Her approach underpins much of this work.48

In the context of these frameworks, I observed some key qualities of good data poverty interventions. These are not qualities of internet which are important to every user. They are the qualities of good interventions from the perspective of a user facing social disadvantage and more likely to be facing data poverty.

Qualities of a good intervention for users facing data poverty

- Private spatially: as internet use has changed, we now more than ever carry out our intimate lives online. Privacy is dignity. Any internet solution in the UK must allow someone to look up health conditions they are worried about, talk to a counsellor or take a video GP consultation, without having to share this experience with those around them.

- Private digitally: the online world is brimming with opportunity, but inevitably also risk. Secure connections are necessary to submit personal information on benefits forms, do online banking, or complete medical questionnaires. Users must be safe on a private connection.

- Decent quality: individuals need a connection with good speeds, enough data allowance and low latency. Having good speeds is not a luxury; it is critical for families sharing WiFi connections or for data-hungry activities such as working from home. Low latency is important for work or classroom learning, but also to enable social connection. Recent evidence shows high latency interrupts communication and reduces the sensation of a shared reality. 49

- Quick to access: individuals in this user group need internet now, not in a month, six months’ or two years’ time. They need to fill in daily Universal Credit journals, renew their prescriptions, speak to someone during a mental health crisis – these are essential services that cannot wait.

- Affordable: Affordability is complex; the internet has shifted closer to a utility than a luxury. Families and individuals are totalling up rent, energy and food bills and are cancelling their broadband. What is affordable for one household is not affordable for the next.

- Sustainable: the pandemic threw a spotlight on internet access, how it is essential and how many people do not have good access. The responses to address the connectivity crisis were impressive, but short lived. We need new solutions that can bridge into the future50.

- Portable: many people in financial hardship or social crisis move around a lot. An asylum seeker, a woman fleeing domestic violence, a person who has recently lost their job and is sofa surfing; they need internet to sort out documents from abroad, speak with trusted friends or look for work. They need internet they can take with them wherever they go next.

- Plug and play: many people without good internet access don’t have essential digital skills. The friction of understanding tariffs, navigating installation and device set up is too complex. Simpler options work better.

- Pause available (or no contract): Poverty is unpredictable. Low-earning workers have less savings, are more likely work unpredictable hours and have a smaller budget. Financial instability is consistent across many groups facing data poverty; a fridge breaking, an unexpected gas bill, or reduced hours can eat up the small amount left over each month. Solutions with pause options (like a gym membership) or without contracts are much better suited.

Comparison matrix: models at a glance

This matrix shows at a glance which models have the qualities of a good intervention for this user group. The analysis which follows goes into detail.

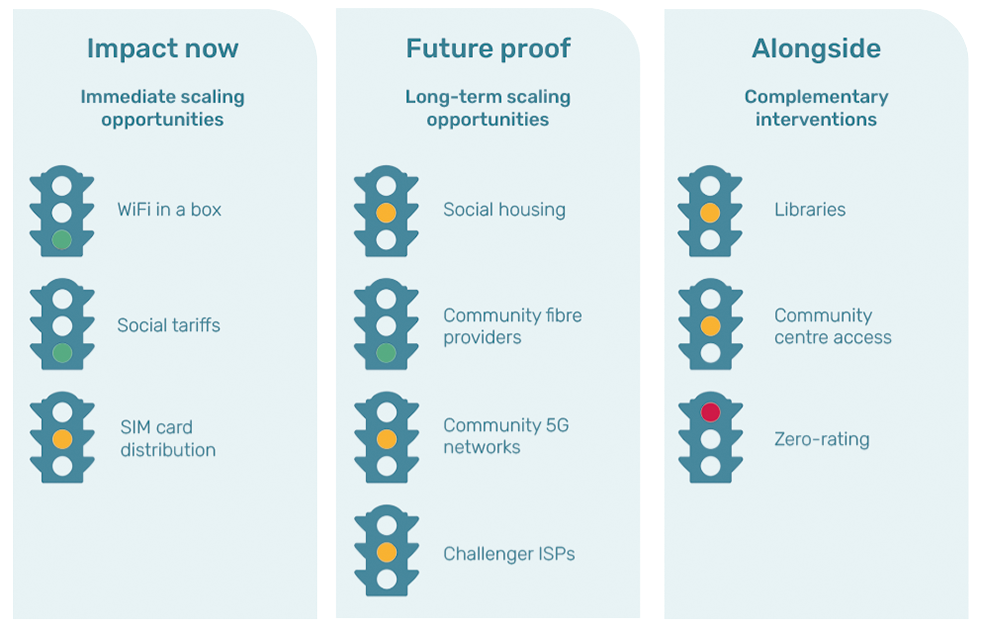

Overall scaling recommendations: solutions to data poverty

Through analysis, the models for tackling data poverty are categorised in 3 ways:

- Impact now: initiatives which could be scaled with immediate effect

- Future proof: initiatives which will take longer to implement but could have long-term impact

- Alongside: initiatives which will never be the solution to data poverty, but can complement other initiatives

The traffic lights indicate which are most ripe for scaling. WiFi in a box, social tariffs and community fibre providers are identified as the top three initiatives most ripe for scaling.

Existing solutions: A comparison of different models

What follows is an in-depth analysis of each of the models, with case studies to illustrate.

WiFi in a Box

WiFi in a Box is any device which offers broadband speeds and connection to multiple devices, via a portable device in the home fitted with a SIM card. This means a home can have internet that feels like broadband, without installing a fixed line network connection.

Pros:

- Private spatially & digitally: unlike public WiFi connections, broadband in a box can be used in the home as a private connection. Giftable schemes can be private to the user.

- Multiple user: SIM-enabled tablets or phones can only be used by one person at a time; WiFi in a box can support a whole household, with privacy.

- Quick to access: it can take as little as a few days to request, post and set up this solution. This was a key reason for adoption in some large areas across the UK, such as Connecting Scotland.

- Pause available: Broadband to the home requires installation costs and a monthly contract. WiFi in a Box is the cost of the router or MiFi and then a monthly data cost. Some social enterprises offering WiFi in a box offer an option to pause the service for no charge or penalty, and often without a contract.

- Affordable to user: Costs to the user range from £7-£20 a month; a competitive rate for home internet. Users report being pleased with the price, speed and data amount. The cost of posting a lightweight device to an address is minimal, and the plug and play set up means technical support can be remote.

- Giftable – Various providers have found ways to gift or loan WiFi in a box. This means family members can get a box for relatives or a charity can buy it on behalf of someone who would struggle to get a fixed line broadband without a credit check or bank account.

- Sustainable long term: with the roll-out of Fixed Wireless Access, much internet access relies on a combination of fixed cable and mobile access. Although there could be issues with high data usage, for many users needs, this is a good short to medium-term solution.

- Plug and play. The device is a single box with one plug, which uses mains electricity or is battery-powered (known as MiFi). Customers put the box upstairs, near a window and use mobile signal (4G/5G). This requires minimal digital skills and can be set up by the user.

- Portable: the solution is not fixed to the premises. This is ideal for customers in an unstable housing situation; installing fixed broadband makes little sense when a customer knows they will likely have to move before the contract time is up.

Cons:

- Privacy: If a charity contracts directly with the ISP for SIM cards, the organisation can be partially liable for spurious activity and individuals will struggle to monitor their data allowance. Organisations have got round these challenges, but it could be difficult for smaller organisations without easy access to legal advice.

- Plug and play: Not all users feel confident positioning a box to get good signal (it needs to be high up in a house, near a window). If the mobile coverage to that location is poor, this can affect speed and latency.

- Sometimes decent quality: Speeds vary based on mobile signal strength and number of devices using concurrently. Advanced versions of ‘WiFi in a box’ have user management which allows multiple users to be online without slowing speeds.

- Large buildings with brick infrastructure have limited mobile reach, meaning some shared accommodation projects have faced quality challenges.

- Could be sustainable long-term: Infrastructure challenges Fixed Wireless Access (FWA) – the ability to access the internet via mobile networks – means more customers have to share access with mobile users. Areas of high mobile demand might mean that the service is unreliable.51

- Data allowances: large data allowances may be needed to cover a household’s use. Some communities found that a 20GB data allowance was used up quickly by a family watching BBC iPlayer, and ‘Unlimited’ packages actually throttle (slow down) speeds after a certain amount is used. Cheaper MiFi units can be very data hungry, using up allowances quickly.

- Sometimes unaffordable: currently the box ranges from £75-225, depending on the model. Some social enterprises and charities use philanthropic funding to cover this, but long-term, a more sustainable option may be needed.

- Telecoms and technical skill needed: the best versions of this model use advanced technology and strong negotiating skills with telcos. Smaller community organisations would need to partner with a larger organisations to navigate some of these obstacles.

Case study – Hartlepower, Hartlepool

Hartlepower, a community interest company based in Hartlepool, offer ‘Get Connected’52, a WiFi-in-a-Box solution. For £20 a month, residents can get a one-plug router posted to their homes. Through a 4G SIM card, they have access to 600GB data per month. They can pause the service at any time with no charge and can call a number on the side of the box to troubleshoot.

Through grant funding, the charity pays for the cost of the router itself (about £75) and staff time to connect and troubleshoot with low- or no-income customers. What began in Hartlepool has scaled regionally and beyond; Hartlepower has now distributed routers to over 1,000 people from Hartlepool across the North East and even to Devon.

Hartlepower partners with a local community-café, Lilyanne’s, who keeps a stock of devices on the premises. When someone presents with a social barrier, such as fleeing domestic abuse, Lilyanne’s staff can offer the WiFi in a box there and then. By combining digital access with addressing social needs, local people are getting a more rounded package of support – to support them as individuals.

Des*, 19, recovering from a heroin addiction describes the impact of a connection:

“Now, I got my Universal Credit stuff sorted, and just staying in contact with my family. It’s good for me mental health as well, there’s a way I can contact my CPN [Community Psychiatric Nurse] online … ask [community worker] to bring me food. Before I had the internet, I couldn’t do none of that.”

Case Study – Get Box, Jangala

Get Box53 is a paperback book-sized internet connectivity device, made by Jangala, a humanitarian tech charity. It produces a secure WiFi network using a 3G/4G SIM card. Get Box can be posted to the user, plugged into mains electricity and can support tens of people in a single household.

As a philanthropically-funded charity and social tech organisation, Jangala has been partnering with UK organisations to gift these boxes and help people in immediate need. Get Boxes have been loaned out to families from schools, set up in women’s refuges and to NHS service users.

GetBox uses remote fleet management software which means Jangala can receive usage information to troubleshoot problems remotely. This results in an increased ability to track impact; many schools or charities give out connectivity devices/SIM cards and cannot tell if or how they are used. Similarly, Jangala can monitor number of users, data transfer and signal strength, helping them understand and learn from usage.

Case Study – The Simon Community, Belfast

In Belfast, 14 Get Boxes were distributed around accommodation for young people in hostels and asylum seekers. The boxes provided internet for 70+ people for over 12 months. This meant residents had access in their rooms, instead of just communal areas, increasing privacy and dignity.

A Project worker reported the difference internet can make for asylum seekers, enabling them:

- Social contact with family overseas during a traumatic time.

- Contact with their home country to obtain documentation and evidence for their case to claim asylum in the UK. This is near impossible without internet access.

- Opportunity for activism, to further their rights and make their voices heard.

- Access to trauma-informed support services; a 12 week creative writing story-telling course to process trauma and share experiences.

Case Study – Mental health, Camden & Islington

Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust partnered with AbilityNet and Jangala to address digital exclusion for patients accessing their services. What began as a pilot, to ensure continued access to psychological support during Covid, expanded to the whole Trust; patients could borrow a device (tablet), internet connectivity (Jangala Get Box or a donated SIM card) and gain digital skills support through AbilityNet.

The partnership with Get Box offered a 6-month loan scheme of a device and connectivity, a ‘stepping stone’ towards digital inclusion for access to therapies and internet inclusivity. Over the first 8 months, 106 service users were referred, with over 50 tablets loaned, and many more supported.

There was an older couple, who were Irish. They called me specifically to tell me that they had been listening to the Irish radio for the first time in like 20 years. And they were like, Oh, this is amazing. It's like being a home again. The songs I never thought I'd be able to hear again, this is the best thing.

Community worker

Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust

Case Study – Connecting Scotland, Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO)

Connecting Scotland 54 is a digital inclusion programme, funded by the Scottish Government and co-delivered with SCVO. The scheme initially aimed to connect 9,000 households impacted by lockdown and shielding requirements, eventually expanding to reach 60,000 households by the end of 2021. Connecting Scotland provides Mi-Fi devices to low-income digitally excluded households.

MiFi devices were chosen because the solution was quick to distribute, set up was relatively easy and could support households with multiple devices. Users reported reasonably good speeds, and a portable device was more suited to client groups who were transient, including people experiencing homelessness.

This project learnt and adjusted over time; the initial 20Gb/month data allowance was upped to unlimited data when some participants reported running out. Some families faced set up challenges (such as MiFis need to be positioned high up, near a window) which the Connecting Scotland helpline (managed by charity People Know How) supported. A small number of the Vodafone SIM cards (c.5%) could not get reception in more rural areas, such as Highland areas and the Orkney Islands. In these cases, the project tried a SIM with a different mobile provider. 55

“I think if we were doing it again, it probably still would be my preferred connectivity option just because of the flexibility and ease of getting it out to people. I think there’s something about the freedom to move around with the MiFi as well. So if you’re moving house, the ease of being able to unplug it and take it with you.” Digital Participation Project Manager, SCVO

Recommendations for scaling WiFi in a box

An ideal WiFi in a box:

- is posted or given to individuals, immediately

- is distributed via charities, community organisations and frontline workers

- has a support line to help with set up

- costs a fixed monthly amount, with no hidden uplift

- has a pause option

- has the boxes (hardware) funded philanthropically or by government

- supports geographically isolated areas with poor fixed line access

- has sufficient data allowance to support a household (ideally unlimited)

Proposed scaling mechanisms:

1) An evolution of the National Databank which offers WiFi in a box devices alongside data gifts. This option banks on existing relationships the databank holds with local organisations and telcos gifting data.

2) Expansion of existing organisations who provide WiFi in a box, eg. Jangala and Hartlepower. Investment from government, philanthropic funders or angel investors could increase reach.

3) Adoption of WiFi in a Box model by community organisations and/or Local Authority Digital Inclusion teams, potentially through a targeted awareness campaign.

Social tariffs

Social tariffs are more affordable internet options available to people claiming benefits. At the time of writing, there are eight broadband social tariffs on offer at the time of writing and one mobile social tariff in the UK.

Research from Which? in 2022 found that customers eligible for a social tariff could save an average of £250 a year by switching from their current deal to the cheapest social tariff. 56

Pros:

- Privacy: Social tariffs provide home broadband or mobile tariffs, creating good opportunity for digital and spatial privacy.

- Affordable: Most social tariffs are more affordable than other internet packages, ranging from £12.50 to £20 a month.

- Exit fees waived: most providers waive the early termination charge (ETC) if a customer moves from an existing contract to their social tariff.

- Sustainable long term: eligibility is binary, based on whether a customer claims benefits or not. This clearly stratifies groups of people who would benefit from the intervention and aligns broadband with existing ways we stratify state support in the UK.

- Equality: in theory, social tariffs reduce geographical variation and increase equity of access, because providers are encouraged to offer a standard package in different parts of the country.

- Pause available: some tariffs offer ‘pause’ options to pause a contract mid-way or rolling 30 day contracts.

- Dignity in transaction: Some argue that there is dignity in transaction and that customers being empowered to choose a social tariff enables them to continue purchasing internet and is more dignified than gifted options.

Service volunteers in an Age UK service in London emphasised that the process for accessing the BT social tariff had got easier in the last year, but many people still didn’t know it existed.

“I don’t think it’s really well publicised. I don’t think there’s a lot of elderly people that realise that they could be eligible for this. It’s a real shame.” Volunteer

Cons:

- Low uptake: Research from Ofcom shows that around 4 million households receive Universal Credit, but only 3.2% had taken advantage of a social tariff as of August 2022. 57 Ofcom has encouraged telecoms to promote social tariffs and called on all broadband firms to offer a social tariff. 58 Further research is needed to understand why uptake is so low. Reasons could include:

- Speeds: Which? surveyed 2,000 individuals eligible for social tariffs and 44% cited fears that the social tariff speeds was too slow as the main reason for not taking up a social tariff. 59 Some providers are upping their speeds and introducing secondary tariffs. See table below for detail.

- Lack of awareness: 6 in 10 eligible households said they were unaware social tariffs existed 60 and many frontline workers are also not aware. Some politicians have attacked telecoms companies for lack of promotion. 61

- Customers must be proactive: Currently, the onus is on the individual to find, purchase and transfer to a social tariff, not an easy process for those lacking digital confidence. Not all consumers have the resources, headspace or digital literacy to find and switch to a social tariff. 62

-

- Exit fees: when a customer exits an existing contract, they often pay a large early termination charge (ETC). Many providers waive this if a customer is moving to a social tariff, but it is unclear upfront if this is the case, which may well put off eligible customers. Some providers mandate customers can only switch to their social tariff; if they move to a competitor’s social tariff, customers must pay the ETC.

- Persuasive sales: some people are put off switching due to the process. Customers often wait on hold for a long time, only to be offered an upgrade or special deal. Some benefit from these offers; many report feeling manipulated.

- Stigma: some customers object to the wording of ‘social tariff’ which can undermine the dignity of the transaction.

- Accessibility: The process of getting a social tariff can be laborious and often requires the customer to provide proof of benefit claim; another set of forms to fill out in a complex life. It is possible social barriers are decreasing access, for example if someone has learning disabilities, language barriers or poor mental health.

- Potential lack of service: some providers take 14 days to switch to a new provider. The idea of a gap in service may put off many people from switching. Being without internet is especially daunting if a customer relies on it for work, disability support, social connection or food shopping.

- Unclear eligibility: the eligibility for social tariffs vary. Some are only available to people on Universal Credit, some include other benefits like pension credits, housing benefit, PIP, and Jobseekers’ Allowance. Some tariffs are only available to existing customers.

- Sometimes affordable: Only some social tariffs have pause options, and they can cost up to £25 a month. For some people, this is still a monthly bill they can’t afford.

- Manual verification: The Application Programming Interface (API) which automatically checks if a customer is claiming benefits was only recently made available to all providers, having previously been open to just BT. This delay may have led some companies to not promote their social tariffs, but greater efforts are required to mandate this promotion now that the API is available.

- Eligibility feels straightforward, but misses key people in need: Many people do not claim benefits due to language barriers, stigma, lack of access (the internet), asylum or immigration status and other reasons. In-work poverty has been steadily rising in the UK for the last 25 years,63 and many people on low or unstable income may be as in need as those claiming benefits. Key groups who are struggling financially are not eligible and miss out on this support.

- Price rises: it is currently unclear how social tariffs will be affected by above-inflation price rises by telcos. In 2022, prices rose around 9%.64 Ofcom allows annual price rises under certain conditions.

- Sometimes decent quality: many social tariffs offer very low speeds, which makes the offer less valuable for some households. Some providers are addressing this; Hyperoptic now offers two speeds of social tariff and Virgin Media O2 recently increased their speeds.

- Geographically restricted: many of the tariffs are only available if the network operates in a customer’s local area.

- Penalising smaller, community-focused ISPs: some smaller challenger ISPs offer low prices and give back to their communities. If these ISPs were mandated to offer a social tariff and many customers switched, this could undermine their commercial viability. They argue this would undermine their wider ethical approach. This offers some argument that if social tariffs become mandatory, this should only be for larger ISPs.

- Portable: most social tariffs offer home broadband and are therefore not available. The exceptions are VOXI, the current mobile social tariff available from Vodafone, and EE.

Fifteen pounds a month is not an affordable social tariff for the people we’re talking about. For some of the people we’re talking about, a fiver is a lot.

Jason Tutin

Digital Inclusion Lead, 100% Digital Leeds

Case study – iConnect, Monmouthshire, Wales

The iConnect Project 65 ran for 6 months in 2022, getting people in the Monmouth Council area access to devices, WiFi, troubleshooting, SIM cards, digital skills, and cybersafety training.

When staff offered a range of options to residents; home broadband, MiFi, SIM cards, most chose home broadband. Social tariffs were easier to implement with some ISPs over others: “the BT one is the one I’ve had most success with” (Digital Inclusion Worker).

They noted that social tariffs, although helpful, were not well known.

“None of the service users we spoke to had heard of them. I mean, I myself hadn’t heard of them until I started researching at the start of the project if I’m honest. They are not very well advertised.” Digital Inclusion Worker

Recommendations for scaling social tariffs

An ideal social tariff:

- is available to citizens claiming key benefits, including Universal Credit, Personal Independent Payment (PIP), Housing benefit, Pension Credit, Jobseeker’s Allowance

- does not incur exit fees from current contract and is clear with customers upfront that this will be waived

- has a clear, accessible switching process (ideally a switching service) available online and offline

- allows customers to move freely between providers

- is well known amongst the public and frontline professionals

- is affordable; costs the user proportional to their income

- is cost-shared between government and industry

- has reasonable speeds (in future this could be defined by the Minimum Digital Living Standard)

- for mobile social tariffs, data allowances should be high; some may be using as primary access

Scaling mechanisms:

Level 1: Awareness schemes to empower customers to switch:

- Mandatory checks and awareness:

- During any customer conversation, a telco could check if a customer is on benefits and eligible for a social tariff.

- Telco websites, when comparing tariffs, could be mandated to show the cheapest options online, including social tariffs.

- Telcos could have to commit to a level of marketing for social tariffs.

- Standard information and options from UC/DWP: When a citizen signs up for Universal Credit or any other benefit, they could be automatically informed of social tariff options.

Level 2: Proactive methods to increase uptake

- Switching service: an internet switching service could reduce friction to switch, either for broadband and mobile services, including to social tariffs. Companies like Nous are already offering this and One Touch Switch offers the beginnings of this.

- A dedicated team in UC could focus on getting eligible people on social tariffs as part of the benefits service.

- Social tariffs could be built into social housing (see section on Social Housing).

Level 3: Systems shifts:

- Opt out: Social tariffs could be opt out, so that when a citizen claims benefits, they are automatically enrolled in a social tariff. Although this might seem unusual in a competitive market, opt out has been demonstrated to have high social impact, for example in organ donation and pensions.

- A government-owned ISP set up to deliver social tariffs, with its own outreach to deliver to benefits claimants.

SIM card distribution

SIM card distribution has grown over the pandemic. SIM cards can be pre-loaded with data, calls and minutes, or topped up with vouchers, which are given directly to the individual facing data poverty.

Pros:

- Private: SIM cards are registered to an individual (usually) and therefore generally provide a private connection. This doesn’t account for device sharing.

- Quick to access: SIM cards can be distributed and set up quickly. Community organisations can apply for SIM cards through a simple online process, resulting in a low burden on community. Organisations and easy in-person or postal distribution to individuals.

- Eligibility: There is no need for benefits paperwork or proof of need. Community organisations can make a swift judgement call on whether a person in front of them would benefit.

- Affordable: SIM donation is often free to the user.

- Plug and play: SIM cards can be easily inserted into an unlocked mobile device and set up by frontline workers with low digital skills. Or, an effectively value-less SIM card can be topped up with a voucher, with an online process.

- Portable: SIM cards can be used in smartphones and tablets and do not require fixed accommodation.

- Gifting: SIM cards are cheap and therefore generally gifted alongside a device. This requires less administration and process than loaning and reduces complications of liability and privacy.

Cons:

- Eligibility: customers must be 18+ to access most databanks.

- Sustainability: SIM card offers are usually time limited; around 6 months. Although there are sometimes renewal options, SIM card distribution tends to be a bridge, leaving users without internet when the time limit expires.

- Frontline worker confidence: A key success factor is the confidence and skills of community workers advising a customer to get a SIM card and helping them set up. Reports of community organisations overestimating distribution and lacking confidence means some SIM cards are stockpiled locally, unused.

- Plug and play:

- Accessibility: Insertion and set up is fiddly for anyone with mobility issues or arthritis. Many customers need support from a frontline worker to set up a SIM and phone.

- Different telcos also provide different processes for activating data each month, which creates friction for users with low digital skills. Frontline workers report that trouble accessing the voucher top up process puts many people off.

- The process for transferring your original number through a PAC (Porting Authorisation Code) is cumbersome and especially difficult for a user with limited digital literacy.

- Process: Prepaid SIM cards usually need to be registered to an individual; the burden of this is usually put on frontline workers, who must manually insert and register each SIM card before distribution to a customer, or who need a live set up session with the customer to make it usable. Where a charity or community organisation registers the SIMs to the organisation, there is some liability risk and it’s harder for individuals to check their data allowance.

- Complexity: Different telcos offer different combinations of data allowances, calls and minutes and different redeeming processes, which adds a layer of complexity in effective distribution. This also creates complexity for frontline workers to navigate, in understanding what packages are available and relevant, and explaining this to potential customers.

- Accessibility: Insertion and set up is fiddly for anyone with mobility issues or arthritis. Many customers need support from a frontline worker to set up a SIM and phone.

- Sometimes decent quality. Some rural organisations report poor signal from donated SIMs. Donation schemes tend to get round this by establishing which provider has the strongest signal and only sending SIMs from that provider to that geographical region. Some people report running out of data, but data allowances have been increased in key instances of this model, creating better access.

Case Study – National Databank

The National Databank 66 was formed in June 2021 by Good Things Foundation in partnership with Virgin Media O2. Vodafone and Three have since joined. In July 2022 Virgin Media O2 pledged a further 15 million GB of free data to the databank.67 Since its launch, the databank has issued more than 50,000 SIMs.

The Databank creates a supply chain of SIM cards from mobile internet providers to local community organisations, who distribute to customers on the ground. This is more efficient for providers and community organisations, who can channel SIM distribution from a centralised source and get them directly to people who need this support most. It is easier for telcos to work with one national organisation, instead of forming individual relationships and implementation processes with schools or charities, although this still occurs, such as to homelessness charities.68

Originally around 3-5GB, the SIM cards now offer 15-20GB a month. Even though not all users use the full allowance, this offers flexibility and peace of mind.

Reports from organisations using the databank are highly positive. Frontline workers appreciated the simplicity of ordering the cards through an online platform (built by Virgin Media O2) and the ease of giving them out. The Databank sits alongside the National Device Bank, which refurbishes and distributes devices to people in need and Learn My Way, free online digital skills courses for beginners.

Case study – Lifeshare, Manchester Digital Collective

Manchester Digital Collective 69 (MDC), a network of organisations hosted by charity Lifeshare, distributes SIM cards to local clients; individuals facing homelessness and social barriers. They offer a 30 minute set up session to help clients get used to their device (smart phone or button phone) and basic digital skills support.

The scheme results in improved engagement with services; it gives case workers a way to contact clients and encourage them to come in for appointment filling out passport forms, identity forms or support work. It also builds trust with the client by helping reduce their social isolation. Interestingly, MDC provides a paper map of WiFi hot spots in the local area, flagging how often their clients rely on a combination of mobile data and free WiFi.

Case study – Chipping Barnet Foodbank

Chipping Barnet Foodbank 70 runs food bank session twice a week. A holistic service, they have distributed around £50,000 worth of fuel and supermarket vouchers and around 600 SIM cards since January 2021. They also channelled SIM cards to refugees through a local charity.

The SIM cards come from Vodafone, who has a national partnership with The Trussell Trust. Chipping Barnet is one of 428 UK foodbanks linked to The Trussell Trust.

With a small core team and a bank of volunteers, the food bank team provides a robust and equal service regarding food parcels but struggles to support everyone with issues underpinning foodbank use. They expressed that they wished they could sit down and help people get set up and offer digital skills.

“It’s difficult to suggest they go onto a [digital skills] café with a child in a pram who doesn’t have any nappies on”.

Volunteer

Chipping Barnet Foodbank

Instead, they would love to have someone on site. “If I could have the SIM cards at the food bank, and that person could set someone up there and then with a phone and a SIM card, that would be incredible.” Foodbank volunteer

Recommendations for scaling SIM card distribution

An ideal SIM Card distribution model:

- uses a National Databank model, enabling local communities to help local people whilst using national partnerships with telcos to ensure good value

- has support at distribution point to help recipients get set up their device

- has champions in each community distribution site with high digital confidence to promote the service

- uses a simplified PAC process (industry-led)

- has high data allowances

- does not include time limits to data access

Social housing

Social housing collaborations create affordable home broadband options for social housing tenants. If internet is considered a right and a utility, there are arguments for treating it more like water or electricity.

Approaches vary; some projects try to create a contract between the Internet Service Provider (ISP) and the social housing provider. Other projects work with Social Housing Providers to endorse a set of tariffs and encourage trust among tenants to switch. Current projects include fixed line and mobile offers.

HACT and Hyperoptic’s report on The Future of Social Housing documents many of the future possibilities well.71

Pros:

- Private: if set up in the right way, social housing options can offer a safe and spatially private connection.

- Reaches a key demographic: because data poverty intersects with social inequality, many of the groups accessing social housing are also facing data poverty and have a delineated audience for marketing campaigns.

- Sometimes decent quality: depending on the agreement with the ISP, fixed connections broadly offer better options but speed throttling on cheaper tariffs can reduce the quality for the individual.

- Highly sustainable: implementing connections to existing infrastructure now helps pave the way for future generations’ needs. For mobile connectivity, using social housing infrastructure for masts or cells could help accelerate much needed 5G infrastructure, especially in cities. New social housing developments could have fibre connections built as standard, to be fit for the future.

- Internet of Things (IoT): social: Smart social housing offers increased independent and safety in assisted living. Wearable smart alarms help those with health problems or a fall risk. Door sensors alert carers when a person with dementia leaves the house at 3am. A voice activated assistant can remind someone to take their medication.

- Internet Of Things (IoT) Environment: Smart social housing offers environmental benefits; collective temperature management, shared solar panels, smart meters and beyond.

- Potential reach to forgotten areas: where social housing is in a more deprived area of a community, installing the infrastructure can create secondary benefit to the surrounding houses and communities by opening up higher speeds at a lower price.